Family caregivers play an important role in states’ efforts to help Medicaid beneficiaries safely remain in their communities. And, as of August 2022, at least seven states (Connecticut, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Missouri, North Carolina, and South Dakota) covered structured family caregiving (SFC) services provided to older adults and/or people with physical disabilities under their Medicaid programs. Coverage of SFC services results in Medicaid payments and other support to family caregivers, usually including spouses and others who are legally responsible for the beneficiary. This brief, which is based on research and interviews with state staff, examines how Georgia, Missouri, and South Dakota are using Medicaid-funded SFC services to help older adults remain in the homes they share with their loved ones.

SFC services consist of a package of services that support home and community-based services (HCBS) waiver participants’ primary caregivers and includes payment, individualized training based on the needs of the waiver participant, coaching, back-up or respite care, and other supports. All interviewees emphasized that they valued SFC services because they enabled HCBS waiver participants who do not self-direct services to receive the personal care they need in their homes from people they know and trust.

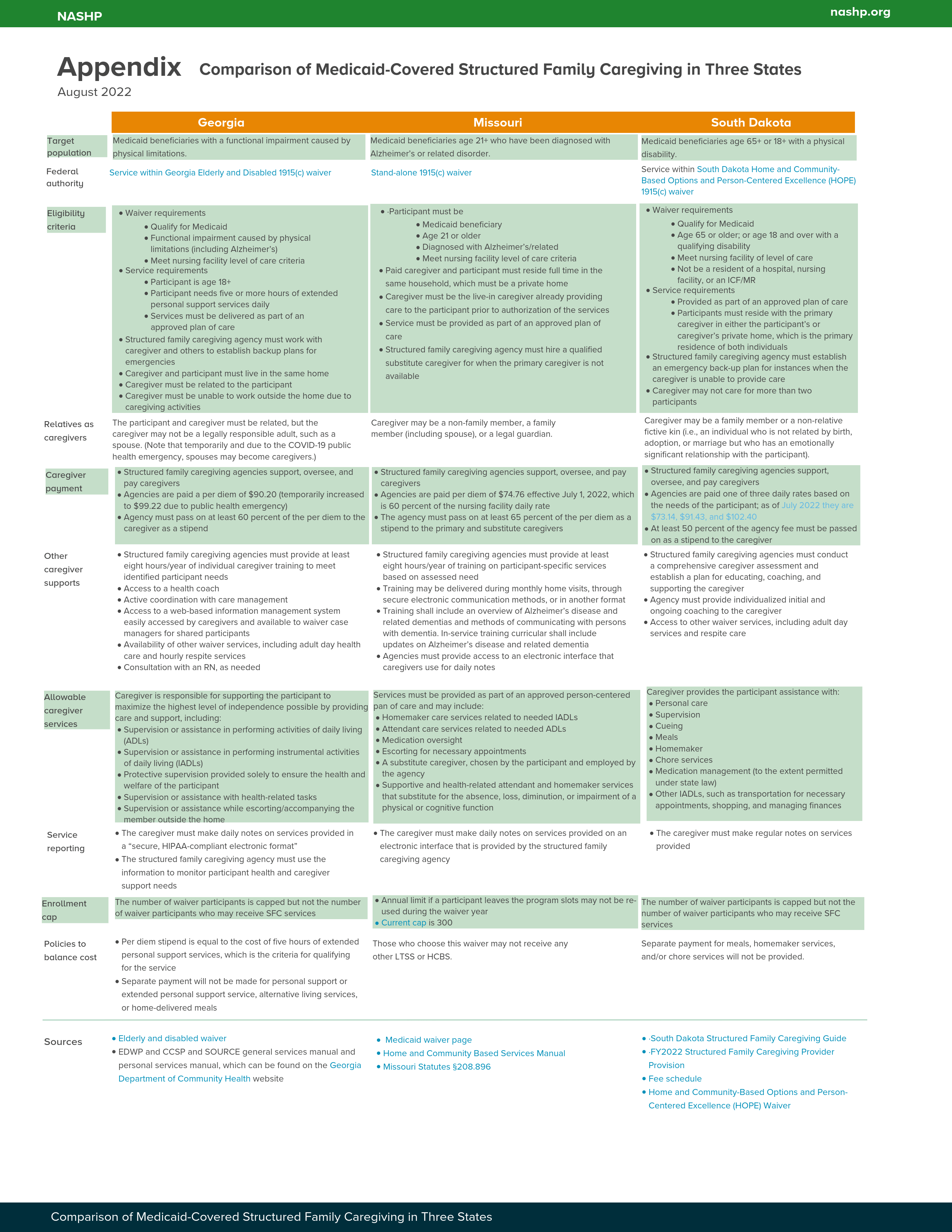

Georgia and South Dakota offer SFC services to both older adults and people with disabilities enrolled in Medicaid. Missouri, however, offers the services only to Medicaid beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s or a related diagnosis. In all three states, Medicaid beneficiaries must be enrolled in an HCBS waiver to qualify for SFC services. As of July 2022, Missouri was providing SFC services to 62 waiver participants, and South Dakota was providing them to 217 participants. Also, all three states administer their SFC services through agencies, which are entities (usually home health providers) that have agreed to provide the services. Interviewees reported that approach enabled their states to implement the service without new staff resources and helped ensure appropriate oversight of the care delivered to Medicaid beneficiaries.

Key Elements of Structured Family Caregiving

“The programs we had prior to SFC you had to be able to self-direct, which as [people with Alzheimer’s] progress they can’t self-direct, which means they have to have a stranger coming into the home.”

— Missouri Medicaid official

There are three key elements of SFC. First is the relationship of the caregiver and waiver participant. In SFC, caregiving is centered in a private home where both the caregiver and participant live. One interviewee described care as being delivered in a residence that is truly a home to both the caregiver and participant. In addition, the caregiver is either a family member or someone who has a significant relationship to the participant. Ideally, the caregiver is already caring for the participant when he or she qualifies for the service, and Missouri has established the existence of a preexisting relationship as a requirement.

Second, SFC is designed to enable the caregiver to make caring for their loved one their primary focus. Payment relieves the financial pressure to work outside the shared home. The individualized support helps caregivers meet participants’ current needs and also helps them plan for changes in participants’ needs and capabilities. A back-up caregiver or respite care enables the caregiver to safely leave the participant to take care of other important tasks, including self-care. South Dakota’s policies ensure that the non-financial supports are appropriately targeted by requiring SFC agencies to conduct a comprehensive caregiver assessment and establish a plan for educating, coaching, and supporting every caregiver. All three states also reinforce through policy the concept that caregiving is a caregiver’s primary focus. Georgia, for example, established the policy that, to qualify for SFC services, the caregiver “must be unable to work outside the home due to caregiving responsibilities.” South Dakota’s policy is to assess each individual case to determine whether the caregiver can hold employment outside the home while ensuring the safety of the waiver participant.

“We talked to family caregivers who said, “I’ve left the workforce for my family member.” Our goal for structured family caregiving is to support these caregivers.”

— Georgia Medicaid official

Finally, SFC includes an element of caregiver oversight. Caregivers are not employed by the waiver participant but rather paid by an SFC agency that is responsible for making sure caregivers are qualified and trained to succeed in completing their specific tasks, that the tasks are completed as needed, and that caregivers respond to changes in participants’ needs. Georgia requires SFC agencies to provide caregivers with web-based support for tracking information, such as daily notes, that is shared between the caregiver, care coordinator, and others. This state also requires the agencies to employ a registered nurse who must be available to caregivers to answer questions about their duties. Also, the nurse, along with each participant’s care coordinator, must visit participants in their homes at least once each month.

Federal Authority to Cover Structured Family Caregiving in Medicaid

All three states implemented SFC services via a 1915(c) waiver. However, Missouri implemented the service under a waiver that delivers only SFC services, while both Georgia and South Dakota implemented it within an existing waiver that also covers other services.

“Over time, this proposal [allowing legally responsible family members to be paid caregivers] evolved into, ‘in what situation would that spouse or that legal guardian really be beneficial?’ That’s where it ended up with the Alzheimer’s focus.”

— Missouri Medicaid official

Opting to implement the service via a stand-alone waiver is enabling Missouri to test the risks and benefits of paying legally responsible family members to provide personal and home health services to waiver participants on a small scale by offering the option to those they feel will benefit most from the option (i.e., beneficiaries diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or a related condition). This approach also enabled the state to tailor policies to the specific needs of that population.

“Oftentimes there are additional services that we can provide on top of structured family caregiving. If they need a nurse, we’ll still provide them a nurse. It’s really focusing on supports in the home that already exist and trying to support those and expand around them.”

— South Dakota HOPE waiver manager

Adding SFC as a new Medicaid service within an existing HCBS waiver enabled Georgia and South Dakota to leverage some of the other services provided under the waiver to support the caregiver and participant. In addition, South Dakota allowed in-home provider agencies serving participants in the home and community-based options and person-centered excellence (HOPE) waiver to hire spouses and other close family to care for their loved ones before implementing SFC services. This state views SFC as a way to bring more oversight while also reducing the administrative requirements that family caregivers need to meet. (For example, family caregivers hired by in-home provider agencies would have been required to provide electronic visit verification for all services provided to participants while caregivers paid for providing SFC services do not.)

Qualifying for Structured Family Caregiving Services

“We didn’t need non-monetary resources. The team of 50+ [waiver] coordinators we already had in place was sufficient to provide this additional service in the state.”

— South Dakota HOPE waiver manager

All three states were able to leverage their existing administrative structure to administer SFC services and were thus able to implement the service without new staff. As is standard under HCBS waivers, waiver participants receive an individual assessment from which a person-centered plan of care is developed and regularly updated. Therefore, SFC services, like other waiver services, are only provided as part of a waiver participant’s approved plan of care. As part of plan development, care coordinators assess whether the participant is in a living situation that meets SFC requirements. (i.e., living in a home with a family caregiver who meets much of a participant’s personal care needs and whose primary focus is caregiving).

All three states anticipate that providing SFC services will prevent the need for some other services. They have therefore put policies in place to prevent separate payment of other services that the caregiver is expected to provide such as homemaker or personal care services. Missouri, for example, states that people with Alzheimer’s disease who choose the SFC waiver will not be eligible for any other HCBS or long-term services and supports. South Dakota specifies that it will not provide separate payment for meals, homemaker services, and/or chore services to HCBS waiver participants who receive SFC services.

Caregiver Payment and Training

The amount paid to SFC agencies governs the stipend amount paid to families and varies widely among the three states (Table 1). This variation may stem from differences in the rate basis. Georgia bases SFC payment on the cost of providing extended personal support services. Missouri bases it on the cost of nursing facility care, and South Dakota bases it on the cost of providing assisted living services.

Table 1: Structured Family Caregiving Payment Policies in the Three States: 2022

| Georgia | Missouri | South Dakota |

|

|

|

The three states also all require the agencies to provide training to family caregivers. Both Georgia and Missouri require agencies to deliver at least eight hours of individualized training per year. Further, the training must be based on the specific assessed needs of waiver participants. In addition, Missouri requires the training to include “an overview of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and methods of communicating with persons with dementia. In-service training curricular shall include updates on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia.” Although South Dakota does not require agencies to deliver a specific number of hours of training, it does require agencies to conduct a comprehensive caregiver assessment and establish a plan for educating, coaching, and supporting the caregiver.

Lessons Learned

“That’s our job, to keep people in their homes for as long as it’s safe and the best place for them to be. That is the outcome that we’re seeing with these individuals.”

— Missouri Medicaid official

States have found SFC services are achieving their purpose. Missouri, whose program has only been operating since July 2021, reports that it is observing the outcome sought — that individuals are able to stay home and be cared for by their loved ones. South Dakota has seen enrollment grow more quickly than expected. This state implemented SFC in 2019, and by July 2022 over 200 waiver participants were receiving the service — a level administrators had not expected to achieve until 2026. Administrators attribute this achievement to family caregivers’ eagerness to make caregiving their primary focus while still being able to pay their bills. Georgia began providing the service in 2019 and, per its 2022 waiver renewal (PDF), plans to continue to provide SFC services into the future.

The three states needed funding to pay for the SFC services; however, two of them were able to fully offset the new costs with savings on other services. Although state Medicaid agencies were able to implement the program without the need for more administrative resources, they did have to secure resources to pay for the cost of services. Missouri’s Legislature added a total (state and federal) of $4.2 million to the Medicaid budget for state fiscal years 2023 to fund the 300 slots for the SFC program. Georgia (PDF) redirected the cost of providing extended personal support services to waiver participants needing more than five hours per day to fund the SFC services. To make certain that amount was sufficient, the state calculated the payment amount based on the cost of those services and established a policy that those who received SFC services could not also receive personal support or extended personal support services. South Dakota assumed that most of those moving into SFC services would be among those whose family members were, at that time, employed by in-home provider agencies to care for their family member.

Participants and caregivers chose to receive SFC services for the payment, but they also find the support services valuable. One interviewee explained that the most important thing that participants wanted was a sense of normalcy — not having strangers come into the home to provide care. The stipend enabled participants to have that because it allowed family caregivers who were already living with and providing care to participants to provide that care without worrying about how doing so would affect their family’s financial situation. Interviewees from both Missouri and South Dakota went on to describe some of the key supports, which included the training provided by SFC agencies, having access to a nurse to help them better understand their tasks, and emotional support for the caregiver, including connecting them to caregiver support groups.

“Make sure you’re supporting the caregiver as much as the care recipients. We have to have that support for both. Money is a big focus, but I do also feel they want support from the [SFC] agency too.”

— Missouri Medicaid official

SFC agencies are critical to providing SFC services. The three states all administer SFC services through agencies that pay, support, and oversee participants’ caregivers. Missouri, for example, has SFC contracts with 69 of the almost 1,700 home health agencies that serve Medicaid beneficiaries. Many of these agencies served participants while they were still able to self-direct their care and did not want to give up that relationship as participants’ conditions worsened. These agencies chose to enter SFC contracts so they could continue serving these participants after their conditions progressed to the point where they could no longer direct their own care. SFC services do, however, place the agency in a different role, and Missouri officials found that they had to work with agencies on an individual basis to help them fulfill their role. Most common were questions about stipend payment and daily documentation requirements. In South Dakota, three of the 82 in-home provider agencies serving Medicaid beneficiaries offer SFC services. One of these agencies provided a similar service in another state, and all providers were familiar with the needs of caregivers and home and community-based service provision, so all were able to understand and meet the administrative requirements.

“[Caregivers] appreciated the oversight they received from our Structured Family Caregiving providers that they didn’t [previously] receive from the provider agency when it comes to caregiver burnout and just being overwhelmed in the whole process of being a caregiver.”

— South Dakota HOPE waiver manager

Summary

States can and do support caregivers — and some states are looking to support family caregivers by covering structured family caregiving services in their Medicaid programs. These services enable Medicaid beneficiaries to receive the personal care they need in their home from someone they know and trust. As South Dakota’s HOPE waiver manager put it, “In general the success of this program has been allowing [waiver participants] to feel like their life is not any different. Even though they maybe had a significant change on their health side, they still can have their loved one providing care, and it can even be enhanced.”

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Medicaid program administrators from Georgia, Missouri, and South Dakota for their assistance in helping us to better understand structured family caregiving in their states. NASHP especially thanks those who participated in interviews: Caitlin Clarey, South Dakota’s HOPE waiver manager; Melanie Highland, director of senior and disability services; and Rena Cox, bureau chief, long-term services and supports at Missouri’s Medicaid agency. NASHP also thanks Catherine Ivy, Georgia Department of Community Health, for her participation in a NASHP webinar from which we drew key information.

This project was made possible by support from The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award totaling $992,990 with 75 percentage funded by ACL/HHS and $247,253 amount and 25 percentage funded by non-government source(s). The contents are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by ACL/HHS, or the U.S. government.