As development of a COVID-19 vaccine continues, states are racing to develop vaccine distribution plans and are eager to ensure that the administrative challenges of testing and personal protective equipment distribution are not repeated. They must orchestrate vaccine storage and administration, data tracking, and capacity issues while questions about who will ultimately pay for the massive vaccine deployment, how it will be equitably distributed, and effective vaccine messaging require a uniform federal response for best results.

Last month, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released the COVID-19 Vaccination Program Interim Playbook for Jurisdiction Operations. Its publication launched a 30-day deadline for states to create and submit their plans for vaccine-ordering, storage, and handling to the CDC by Oct. 16, 2020. The playbook, which acknowledged there are many unknowns and unanswered questions, will be continually updated by the CDC as guidance and best practices are refined. Recently, the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) convened a cross-sector group of state officials to discuss their distribution strategies. The questions they raised are explored below.

How will the costs of preparation and planning for vaccine distribution be funded?

With CARES Act funding, the Department of Health and Human Services is distributing $200 million across 64 jurisdictions through the existing Vaccines for Children Program (VFC) for vaccine preparedness and planning. The funds are targeted to ensure jurisdictions can develop and update plans for their eventual vaccine distribution. These funds are used to ensure states’ Immunization Information Systems (IIS) are ready to accept all vaccine information, and that providers are enrolled and connected to the system to input their information, among other planning tasks. However, the CARES Act funding allocation uses a population-based formula and is not intended for other expenses related to vaccine administration, such as PPE, and must be spent by the end of 2020. With states already facing limited capacity given current budget constraints, these spending restrictions are expected to further strain state budgets, which could negatively impact their ability to distribute the vaccine to their most vulnerable populations.

There is currently no unified federal plan for distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine, leaving questions unanswered and states in the lead.

States will need to plan to store, administer, and track the COVID-19 vaccines, all while addressing vaccine hesitancies, ensuring equitable distribution, and addressing budget crises caused by the pandemic.

“We need clarity [from the federal government] around financing early on, especially now that states are beginning to see the budget projections’ People will take a more measured approached, and it would be helpful for plans to have a better idea of financing early on so they can plan and get ahead of the vaccine distribution and approval.”

– State Medicaid Official

State leaders also raised concerns about a variety of challenges they face in distributing the COVID-19 vaccine, such as a lack of clarity on federal funding for vaccine administration, refrigeration and storage, and availability of state funding.

According to the CDC playbook, the federal government will procure and distribute the vaccine and any associated supplies (including needles, syringes, and limited masks and face shields) at no cost to providers. Typically, insurance reimbursement to providers includes the cost of the vaccine itself and some of the associated administrative cost. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) recommended in its framework for equitable vaccine allocation that vaccines be made available at no cost and that administration of the vaccine be adequately reimbursed. However, it is unclear how administrative expenses will be covered and by whom.

Other complications to state planning efforts include:

- What and how many vaccines will be rolled out, and over what time periods; and

- What refrigeration temperature requirements will be.

For example, given the storage and temperature requirements of one COVID-19 vaccine currently in clinical trial, states are concerned about additional costs of storing, freezing, delivering, and administering vaccines. CDC, meanwhile, has instructed states not to invest in ulta-cold freezers yet.

Vaccine administration can also be prohibitively expensive for facilities. Because there are still so many unknowns about which vaccines will be available and how they will be transported, details about who will ultimately finance these costs are still being finalized. State officials expressed concern that as they face budget crises and limited federal information and regulations, they are being set up to fail.

Who will be the first to be vaccinated?

The CDC recommends that states establish COVID-19 vaccination program implementation committees with representatives from every sector and from communities. The NASEM framework highlights the need for equal regard, maximization of benefits, evidence-based actions, and transparency in decision-making. NASEM and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) have been discussing how to prioritize the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine to critical populations, but delayed making a final decision until a vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for clinical use.

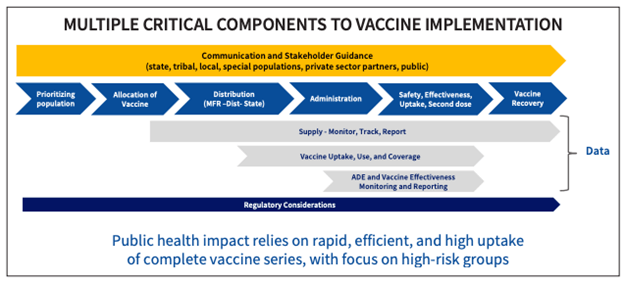

Source: CDC COVID-19 vaccine implementation presentation, July 29, 2020.

The CDC playbook highlights a phased approach to distributing the vaccine and delineates three phases of distribution. However, during Phase 1, which has a limited supply of COVID-19 vaccine doses available, states are encouraged, but not required, to focus their initial efforts on reaching critical populations, including:

- Health care personnel who are likely to be exposed while treating people with COVID-19;

- Those at increased risk for severe illness, including those with underlying medical conditions and people age 65 years and older; and

- Other essential workers.

These phases align closely but differ slightly from NASEMs equitable distribution framework for Phase 1.

Most state officials noted they intend to follow this guidance for prioritizing an equitable vaccine distribution. But, some states also noted concerns regarding using their immunization systems to identify and distribute the vaccine to these populations, especially to those who live in large, sparse, rural, and frontier areas with smaller public health administrative capacity. Others raised concerns about whether individual providers will be able and willing to administer the vaccine, and if they can do so in a way that follows the equitable allocation framework. Their concerns are tied to cost and reimbursement levels, as well as physical capacity to store and refrigerate the vaccines. Additional federal guidance and funds could alleviate these issues.

Who will pay for the vaccine and associated costs?

The NASEM framework recommends that the COVID-19 vaccine be provided and administered with no out-of-pocket costs. Paul Mango, HHS deputy chief of staff for policy, said the agency’s goal is for the COVID-19 vaccine to be free for all Americans. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, similarly noted, “The vaccine itself has already been bought by the federal government – A person who gets a vaccine will not pay for the vaccine.” However, Fauci did note that patients could be charged for costs related to the vaccine’s administration. Confusion remains about how these decisions will be made and it remains unclear how administrative expenses will be covered and by whom. For example, in the VFC Program, a provider who administers a qualified pediatric vaccine to an eligible child may not impose a charge for the cost of the vaccine, but can charge a fee for its administration as long as the fee does not exceed the costs of the administration.

ACIP has not yet issued a recommendation on state coverage of a COVID-19 vaccine, but Section 2713 of the Public Health Service Act requires mandatory coverage of all ACIP- recommended vaccines for state Medicaid expansion programs and most commercial health plans (state-based exchanges). ACIP-recommended vaccines are considered preventive and therefore are not subject to cost-sharing by patients. In March, Congress added a COVID-19 vaccine to the list of vaccines commercial health plans are required to cover. Usually insurers have up to a year after a vaccine is recommended by ACIP to implement coverage, but the CARES Act drastically speeds up this timeline by requiring plans to cover a COVID-19 vaccine within 15 days of its approval. The Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Act specified that a vaccine should be priced “fairly and reasonably.” And, US officials noted over the summer that they expect insurance companies will not charge copays for COVID-19 vaccinations.

The cost of the vaccine for Medicaid enrollees is expected to vary by state. While Medicaid expansion states require complete coverage of ACIP-recommended vaccines without cost sharing, vaccine coverage is optional in non-Medicaid expansion states and remains up to the state’s discretion. However, through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, all states are eligible for a temporary (through the end of the public health emergency) 6.2 percent increase to their Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). One condition for states to receive this money is that the state plans must cover, without cost sharing, COVID-19 vaccinations.

For Medicare enrollees, vaccines are typically covered under Medicare Part D, which allows for cost sharing. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) can opt to cover the COVID-19 vaccine under Medicare Part B (which already covers the influenza vaccine and the pneumococcal pneumonia vaccine), a move that would prohibit cost sharing. As of mid-September, officials were still working with Medicare to figure out the cost to beneficiaries, but noted that the cost would likely not exceed $3.50 out of pocket per individual.

How will states monitor vaccine distribution?

The CDC is developing a Vaccine Administration Management System (VAMS) to manage vaccine administration and provide real-time data from mass-vaccination clinics to federal agencies and state public health departments. The system, funded by an almost $16 million sole-source contract, is designed to share data with existing Immunization Information Systems or immunization registries used by states and territories to record vaccine administration, order vaccinations, and send out vaccination reminders to patients. As of Oct. 7, 2020, however, VAMS has not yet announced plans, leaving state leaders confused about how to plan for vaccine tracking. Concerns have been raised that VAMS might bypass state systems, leaving states unsure whether they will need to use the new system or be able to enhance their existing immunization registry systems in time.

Immunization registries – either VAMS, IIS or a combination of both – will be needed to record vaccination information, identify individuals in need of a first or second dose of a vaccine, remind individuals to get vaccinated, and track follow-up. One critical concern is whether immunization registries have the capacity to ensure that people receive a second dose of the vaccine within an acceptable timeframe and that they receive the same type of vaccine for both doses.

Historical underinvestment in IIS has resulted in wide variation across states’ IIS policies, size, and scope. They have different patient consent policies, reporting mandates, and data-sharing policies. In some states, provider participation in the IIS is mandated by law, and in other states participation is voluntary. As a result, only 55 percent of immunization programs have 95 percent or more of individuals in their jurisdictions registered in their IIS. There is also inconsistent communication between systems. Many electronic health record (EHR) systems are not connected to immunization registries, leaving individuals who receive vaccines at different locations with incomplete immunization records. Although some states receive matching funds available through the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) to enhance interoperability of electronic data exchange between EHR and immunization registries, many rely on the CDC, private foundations, and health care providers and insurers to fund their systems.

Because multiple COVID-19 vaccine doses are forecast to be required, strong data-sharing capabilities between registries also is critical. State IIS need to be able to talk to other health records systems and other states’ immunization registries in order to ensure that individuals receive the correct second dose at a different facility, and even in a different state if necessary. However, in 2018, only 10 percent of immunization registries had conducted at least one query of an IIS in another jurisdiction. While the need for better systems to distribute and monitor the COVID-19 vaccine is clear, because VAMS has not yet released plans, states are left to figure out whether and how to:

- Upgrade existing systems, which requires time and resources;

- Rely on a new system that will be unfamiliar to providers and clinics; or

- Use a combination of both.

How are states promoting public trust in the vaccine?

Vaccine hesitancy will also be a critical issue. According to a recent Pew Study, the number of adults who say they will get a COVID-19 vaccine has fallen from 72 percent in May 2020 to 51 percent in September. Another study found that 35 percent of Americans would not get a vaccine, even if it were free. Mistrust of health care is especially prevalent among Black communities, who are skeptical of the medical system because of current and past discrimination against people of color. This distrust continues as Black Americans are hit hardest by COVID-19, making it even more critical that the government finds ways to boost confidence in COVID-19 vaccine safety.

The need for standardized public health messaging during this pandemic is also clear. In fact, state officials noted that currently, clear and consistent vaccination messaging is one of the biggest issues that states need the federal government to address. Typically, states use a variety of mechanisms for disseminating vaccine information, such as partnering with community organizations, hospitals, and other state agencies to disseminate information to their constituents, sending out clinician letters to providers and pharmacists, and using IIS to send vaccine reminders to patients. These strategies will continue to be important when states market the importance of getting the COVID-19 vaccination.

At the same time that state officials are concerned about gaining and developing public trust in the vaccine, they also need to manage expectations about vaccine availability and efficacy. As noted, the CDC playbook asks jurisdictions to plan for three phases of distribution:

- During Phase 1, critical populations such as essential workers and high-risk individuals are prioritized;

- In Phase 2, limited doses will be available to the public; and

- In Phase 3, there will be sufficient vaccine supply for the entire population.

Public health officials are tasked with instilling confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine and conveying the importance of getting vaccinated to the general public, while simultaneously making it clear that most individuals will not be able to get vaccinated until Phase 2 or 3, which is anticipated to start in fall of 2021. Until that point, and even after, individuals may still need to take other effective measures to present the spread of COVID-19, including social distancing and wearing masks.

State leaders are already concerned about this shift in messaging between phases, and worried about overpromising outcomes without increasing anxiety about the vaccine’s efficacy. In order to help manage expectations about when the vaccine may be available to the public while also combatting vaccine hesitancy, consistent messaging across federal and state agencies is urgently needed.

What partnerships are needed at the state and local levels to ensure seamless vaccine distribution?

As highlighted in the CDC playbook, the pandemic vaccination response requires collaboration among many public and private stakeholders to create and implement plans. State officials at the NASHP meeting noted the complexity involved in rapidly developing plans across agencies and across the public and private sectors.

Officials also raised the issue of involving pharmacists as vaccinators, and onboarding them into IIS. While all 50 states do currently allow pharmacists to vaccinate adults, and recent federal action gives state-licensed pharmacists authority to provide the COVID-19 vaccine to persons age 3 and older, only some states have pharmacists enrolled in Medicaid and the VFC program, with some pharmacists citing difficulty in being reimbursed during previous public health emergencies. Some state officials raised concerns that using pharmacies as immunization access points for COVID-19 could disrupt care in medical homes, particularly for children (although children will not be included in the first round of COVID-19 vaccines.) While the playbook highlights the need for increased access to the vaccine to ensure equitable distribution, states are considering how to balance widespread access to the vaccine with maintaining the importance of medical relationships within existing networks.

What federal leadership is needed?

Despite guidance provided by the CDC, there is currently no unified federal plan for distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine, leaving questions unanswered and states in the lead. States need to plan to pay for, store, administer, and track the COVID-19 vaccines, all while addressing vaccine hesitancies, ensuring equitable distribution, and addressing budget crises caused by the pandemic. State officials predicted that logistical issues will be worked out, but the messaging and finances require a uniform federal response for best results. NASHP will continue to track state and federal preparation for COVID-19 vaccination distribution and engage states in identifying challenges and developing appropriate policy and programmatic responses.

CDC-recommended representatives on state COVID-19 vaccine implementation committees:

- Emergency management agencies

- Health care and immunization coalitions

- Local health departments

- Health systems and hospitals (including critical access hospitals for rural areas, in-patient psychiatric facilities)

- Community and rural Health Clinics (RHCs)

- Pharmacies

- Long-term care facilities

- Businesses and occupational health organizations

- Health insurance issuers and plans

- Education agencies and providers

- Correctional facilities

- Churches or religious leaders and institutions

- Tribal leaders

- Organizations serving racial and ethnic minority groups

- Organizations serving people with disabilities

- Organizations serving people with limited English proficiency

- Community representatives

- Entities involved in COVID-19 testing center organization

“The biggest way to avoid the testing mess [is] national leadership. [Testing] was such a mess because states were competing with each other to get supplies.”

– State health official