Faced with limited vaccine supplies, a slow rollout of federal funds, and new federal guidelines allowing vaccination of those 65 and older, states face distribution challenges as they quickly evaluate which mass immunization practices are most effective.

Last week, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced new federal recommendations to vaccinate everyone 65 and older and adults with pre-existing conditions. HHS directed states not to wait to finish Phase 1A vaccinations of health care workers before beginning vaccination of seniors.

While new federal guidance has spurred some states to pivot their distribution strategy, others had already begun vaccinating older residents more widely. With nearly 12.3 million doses administered of over 31.2 million total doses distributed, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), many states are finding different ways to quickly get these shots into the arms of their residents. According to reports, about 39 percent* of total distributed doses have been administered nationally, while a handful of states have exceeded that rate through effective collaboration with hospitals, health systems, and pharmacies.

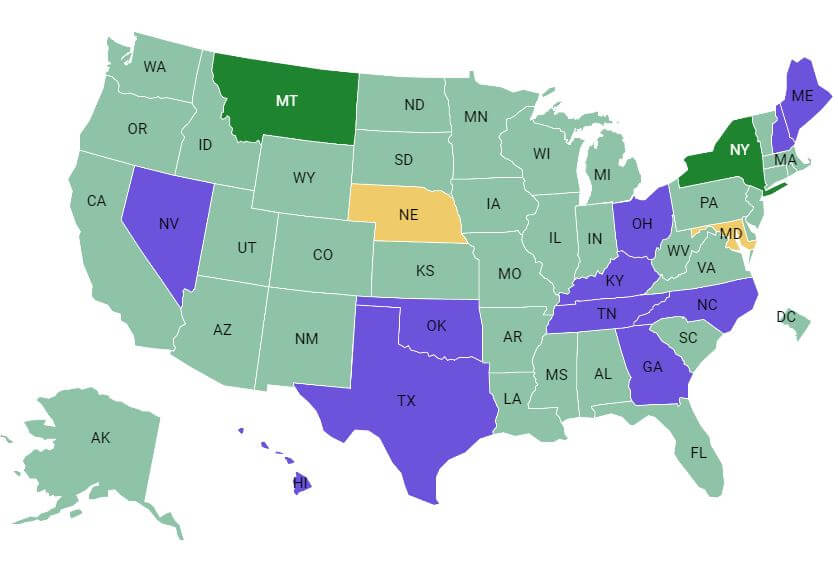

Explore this interactive map and chart to view each state’s priorities for vaccinating specific populations.

Every state is working to vaccinate populations identified in Phase 1A, including health care workers and nursing home residents. Below are challenges and emerging strategies state officials have identified to date in their efforts to vaccinate these populations.

Leveraging Relationships with Pharmacies

To reach residents and staff of long-term care facilities (including skilled nursing facilities that provide higher levels of medical care and assisted living facilities), the federal government partnered with large pharmacy chains, such as CVS and Walgreens, to manage all aspects of vaccine distribution – from storage to vaccine administration. Forty-nine states (all but West Virginia) and Washington, DC signed onto this federal partnership, but the program has proven challenging for states and vaccine roll-out has been slower than expected. While CVS and Walgreens have been able to provide first doses to most skilled nursing facilities participating in the partnership, CVS Health data shows that vaccination of assisted living and long-term care facilities has not yet begun in some states, including Alabama and Indiana. Pennsylvania just activated Part B of its Pharmacy Partnership plan on Jan. 14, 2021, which means pharmacies are only now beginning to vaccinate in long-term care facilities – Part A only provided vaccinations in nursing homes. In Mississippi, vaccination of some assisted living facilities through the federal partnership is not expecting to start until February.

State officials ascribe some of the inefficiency to big chains’ limited personnel capacity, the cumbersome process for getting written consent from residents, and the challenge of obtaining residents’ Medicare information for reimbursement. The federal pharmacy partnership only allows Walgreens and CVS staff to administer the vaccines, rather than partnering with long-term care facility (LTCF) staff. Despite both pharmacies onboarding additional staff to aid in the large-scale vaccination effort, some states, including Mississippi, found that Walgreens and CVS lack the personnel to vaccinate LTCFs quickly and efficiently, causing delays. Additionally, while federal law does not require nursing homes to get consent from residents or family members for vaccination, CVS and Walgreens do. Kaiser Health News (KHN) reports that these requirements have slowed down the vaccination process because they place an additional administrative burden on LTCF staff who must help obtain consent forms and provide patients’ insurance information. KHN noted that states and individual facilities that declined to partner with the federal pharmacy partnership are actually vaccinating at a faster pace.

Other states blame the lag on the structure of big pharmacy chain corporations that may not have had previous experience partnering with LTCFs in their communities. John Vincent, president of the Arkansas Pharmacist Association, explained that because the distribution plan was developed at the federal rather than local level, it does not work for every state or region. CVS and Walgreens, which contract directly with LTCFs under the partnership, have tried to adopt a one-size-fits-all approach to distribution at the federal level, rather than tailoring strategies to the unique needs of local communities.

Maine is also experiencing a lack of communication between the pharmacies and LTCFs, CVS and Walgreens are responsible for contacting facilities to schedule appointments, but without existing relationships, communication and coordination becomes more challenging. Recently, after confirming that Walgreens had unused doses on hand and had not yet scheduled appointments to administer them to LTCF residents, Maine asked the pharmacy to redistribute these doses to two hospitals in need.

However, states that partnered with local, independent pharmacies to distribute and administer vaccines have had more success. For example, West Virginia used a network of over 250 independent pharmacies to distribute the vaccine to nursing homes, LTCFs, and rural areas of the state. These pharmacies already had existing relationships with LTCFs – many of them provide medications, routine vaccines, and more recently, COVID-19 testing services to residents – and therefore already had patient data in their systems. This helped accelerate the distribution process because LTCF facilities did not need to take the extra administrative step of filling out burdensome forms related to consent and Medicare information.

Additionally, West Virginia pharmacies could schedule vaccination clinics at these facilities immediately and on their own schedule, as opposed to CVS, Walgreens, and other large pharmacy chains participating in the pharmacy partnership program. Under the federal program, the large pharmacies scheduled three separate visits to each facility:

- The first two visits are for most residents and staff to get the two doses of the vaccine, and

- The third visit was designed to vaccinate people who missed the first two visits.

But despite this three-visit plan, not all residents and staff were able to get vaccinated, and the limited supply has caused frustrations.

By leveraging existing partnerships and working directly with the facilities, West Virginia was able to identify residents, schedule those vaccine appointments, and secure any required consent forms, all before the state received any of its allotted doses.

Similarly, in Arkansas, 35 of the state’s 350 nursing homes that selected a local pharmacy to distribute the vaccine received doses within 72 hours. In comparison, only 15 percent of the doses that CVS and Walgreens received earmarked for Arkansas nursing homes have been delivered so far. In Washington State, a facility opted out of the federal partnership with CVS after learning the company’s first doses weren’t expected until Jan. 9, 2021. Subsequently, residents were able to receive the vaccine from a smaller pharmacy nearly two weeks early. In Maine, one independent pharmacy, which has been collaborating with LTCFs since 2018 to supply prescription drugs directly to residents, credits its success in reaching and vaccinating residents to the strength of its pre-existing relationship with the facilities.

In Montana, one small independent pharmacy was able to administer about 1,000 doses to LTCF residents in one week, equivalent to the number CVS and Walgreens jointly were able to vaccinate statewide in the same time period.

Collaboration between States, Hospitals, and Health Systems

Most health care workers have received the vaccine through their work venues, such as hospitals, public health offices, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), and tribal health clinics. Doses are shipped directly from the Pfizer and Moderna distribution plants to larger hospitals, which have more storage capacity, and often these hospitals are then tasked with further distributing the vaccine to smaller, more remote facilities. Montana officials cite their close relationship between the state health department and hospital administrators, which includes weekly or twice weekly calls between the two parties, as helpful in rolling out a collaborative vaccine strategy. Montana has administered close to 50 percent of doses received.

Similarly, in Connecticut, where 52 percent of doses distributed have been administered, the state began holding weekly calls with hospitals and state agencies at the beginning of the pandemic to discuss current concerns and future plans, and troubleshoot any emerging problems. State officials believe the constant communication and coordination between state and local partners have helped their vaccine distribution process.

Despite this success, there are concerns that health care workers’ status and facility size and location are impeding their access to the vaccine. Reports indicate that in cities like New York and Boston, more affluent individuals who are affiliated with large hospital systems – but not currently eligible for the vaccine – have been able to obtain doses early. In Delaware, those working in private practices voiced frustration that they have not been able to get doses as quickly as those working at larger facilities. The minutia of distribution is not determined at the state level. As states expand access to the vaccine, it will be important to make sure that socioeconomic status and location are not barriers to vaccination.

Data Tracking/Reporting

Immunization Information Systems (IIS) – immunization registries used by states and territories to record vaccine administration, order vaccinations, and send out vaccination reminders to patients and the Vaccine Administration Management System (VAMS), a CDC system established to manage vaccine administration and provide real-time data from mass-vaccination clinics to federal agencies and state public health departments, are critical to states’ vaccine distribution pans. All states are currently using, or plan to use during later phases, their IIS or VAMS to:

- Identify individuals in need of a first or second dose;

- Track which vaccine and dose each person gets;

- Notify individuals when they are eligible for the vaccine;

- Invite them to schedule an appointment; and

- Send a reminder about second dose appointments.

Many immunization registries also collect patient demographics, such as race, ethnicity, and age, which are useful for tracking vaccination trends and identifying health inequities. States are identifying challenges and solutions for data tracking and reporting.

Streamlining processes for informed consent: Obtaining consent from patients to have their data entered into immunization information systems (IIS) or the Vaccine Administration Management System (VAMS) is an additional challenge. State IIS have varying patient consent policies, reporting mandates, and data-sharing policies. Some states use a opt-in process, meaning that individuals’ data will not be shared in the information system unless the patient or guardian signs a form indicating consent, while other states use an opt-out process, meaning that individuals’ data will automatically be included in the information system unless they, or their guardian, signs a form indicating they choose not to participate in the data sharing program.

Generally, states with opt-out policies have higher vaccination rates and more comprehensive data; state officials have concerns about comprehensive data, especially when using an opt-in consent process. To eliminate these concerns, some states are temporarily changing consent requirements for their immunization registries. In New Jersey, Gov. Phil Murphy issued an executive order changing the state’s IIS system from opt-in to opt-out, and will automatically enroll patients choosing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine into IIS. Patients can disenroll from the registry 30 days after the public health emergency ends. New York waived consent requirements for reporting adult doses into IIS, a step they also took during the H1N1 pandemic.

Ensuring timely and transparent reporting of vaccination progress: With states vaccinating thousands weekly, they are striving to be transparent about how many doses have been administered and who is being vaccinated. Additionally, consistent and timely reporting is critical to determining which areas may be lagging behind in distribution, and which are more successful. Currently, many places are experiencing delays in data reporting to IIS and VAMS, while others are seeing doses under-reported. Providers and pharmacists, already working at capacity, are inputting all of their immunization data into the systems – sometimes by hand – within 24 hours of vaccination.

Some states have begun to address reporting challenges. For example, the Oregon Health Authority is providing technical assistance to vaccine sites to improve the timeliness of data entry into their IIS. In order to improve data collection and reporting, states could consider bringing in additional personnel – either volunteers or hired staff through additional federal funding – with the sole job of inputting data in vaccine databases.

Many states have also developed public-facing COVID-19 vaccine tracking dashboards detailing the status of vaccine rollouts. All dashboards include the number of doses administered, and almost all include counts of how many individuals received the full two-dose series. Many also include demographic information, including county, age, gender, race, and ethnicity. Pennsylvania developed a designated tracker for the type and location of facilities that have received a vaccine shipment. Similarly, Minnesota is publicizing number of doses administered by provider type. North Dakota’s dashboard shows the number of vaccine enrolled provider sites by county.

These dashboards are not only a valuable tool for residents to track progress in their state, but they can also offer insight into current vaccination priorities. For example, Minnesota’s tracker shows that as of Jan. 14, 2021, the majority of vaccines were shipped directly to providers in hospitals, pharmacies, and local public health offices, with several primary care and tribal health sites receiving doses as well. This is in addition to the doses sent directly to LTCFs through the pharmacy partnership.

Prioritizing equity in distribution: Given the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on people of color, states have emphasized equitable vaccine distribution in their plans. However, if states do not invest upfront in strategies such as targeted outreach, hosting clinics in areas and at times accessible to populations of color, onboarding of Black and Latinx vaccine providers, and addressing vaccine hesitancy concerns, officials fear racial disparities in COVID-19 infection and vaccine rates will only increase.

While vaccination rates across states vary very little, and numbers are still low, trends are emerging, including racial disparities. North Carolina’s, early data from its dashboard indicates that, compared to the state’s overall distribution numbers, disproportionately more White and non-Latinx individuals have been vaccinated than Black and Latinix individuals. Additionally, after opening vaccine appointment sign-ups to individuals 65 and older, Washington, DC found that far more people in affluent areas with low COVID-19 infection rates had signed up (2,465 people, in one ward) than individuals in less affluent, majority-Black areas of the city (94 in the ward with the highest death toll had signed up for the vaccine). In response, the district is opening up additional appointments in the neighborhoods with low sign-up rates.

Effective Communication of Vaccine Distribution Information

With vaccination plans rapidly evolving, and public confusion rampant, it has become critically important for state governments to get messages out to providers and the general public quickly and clearly. States are identifying challenges and solutions for effective communication.

Establishing effective ongoing communication with health care facilities and providers: One challenge for states is to make sure that providers are up to date on the latest guidance, especially in identifying which populations are eligible to be vaccinated and when facilities will receive additional doses. In Texas, providers noted the challenge of having a lack of advance notice about vaccine shipment arrivals. In some cases, they had only a few hours advance notice about the first vaccine shipment and cited concerns about not having the necessary staff to set up separate vaccination sites on such short notice. As previously noted, Montana and Connecticut have seen success in distribution due to established and effective communication between the states and their local partners.

Responding quickly to changing needs: Because prioritization guidance from federal and state governments is changing rapidly as the result of the slow vaccination rollout process, some states have opted to use executive orders to quickly communicate new eligibility criteria to localities. In Arizona, Gov. Doug Ducey issued an executive order directing the Arizona Department of Health Services to reallocate vaccines when necessary in order to ensure statewide coverage and rapid administration.

He also ordered counties to publicize the priority population they are currently vaccinating and the location of vaccination sites on their websites.

In Utah, Gov. Spencer Cox used an executive order to extend vaccine eligibility criteria to teachers and individuals ages 70 and older. In the event that providers do not follow these guidelines, the state reserved the right to redistribute the vaccine or reduce supplies during future allocations. For states struggling to get information out to providers and localities quickly, executive orders may be a way to convey new guidelines to a large audience publicly and quickly.

Establishing and enforcing eligibility criteria: Currently, demand for the vaccine is far outpacing the supply. State and local health departments need a system in place connected to IIS to have a waiting list of people ready to receive the vaccine so they can be rapidly deployed. Stories abound about individuals who believed they were eligible for the vaccine and tried to book appointments, but could not. State and local health departments must have systems in place for rapid deployment and need to communicate effectively about how they work, while implementing their carefully considered phased approach. Otherwise, expedience may preempt prioritization, with individuals who have time or access able to jump the line ahead of the most vulnerable.

Many states (including Alaska, Mississippi, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Virginia) and several counties and local health departments have websites that allow individuals to check eligibility and sign up for vaccine appointments or get placed on a wait list. Some individual health care systems have also employed various text message programs. However, some health systems sign-up websites have crashed with overuse, and appointments booked up rapidly. Recognizing that not everyone has access to internet or computers, states have also set up phone lines for booking appointments.

Some states have also had technical difficulties when vaccine tracking systems incorrectly identified individuals for vaccination. For example, in Connecticut, teachers at one school received a notification that they were eligible for the vaccine and made appointments to get vaccinated, when in fact they were not yet eligible under the state’s plan. Those who already were vaccinated before the mistake was corrected will be able to get their second dose, and the Department of Public Health reported that they are putting safeguards in place to make sure this does not happen again.

Colorado also recently changed its priority list to vaccinate those over 70 before essential workers. But, some essential workers, including teachers at a charter school, had already signed up. The state health department encouraged those with existing appointments to keep their appointments, with the assurance that they would be able to receive their second doses.

Vaccine Administration Strategies

As states move to vaccinate new populations, lessons for ensuring sufficient staff and accessible venues will help guide efficient and complete administration.

Authorize a wide range of health care staff to administer the vaccine: The delays in administering the COVID-19 vaccine highlights a nationwide shortage of health care workers. HHS issued guidance in September 2020 to allow licensed and registered pharmacists to order and administer the COVID-19 vaccine to individuals age 3 and older, providing relief from scope of practice laws. Pharmacists have been involved in the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program, administering vaccines in LTCFs and will be instrumental once states begin vaccinating the general public. In other regions, dentists and dental assistants have been licensed to administer the vaccines.

Since March 2020, states have used a variety of policy levers to expand and relax scope-of-practice laws for health care providers in order to overcome personnel shortages. Similarly, given the enormous capacity demands of states’ COVID-19 vaccine distribution plans, many states and the federal government have begun allowing more providers and non-traditional vaccinators to administer vaccines. A December 2020 report by the National Governors Association and the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy found that 20 states had included plans to onboard non-traditional providers, such as dentists and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) in their vaccine distribution plans.

In December 2020, an Oregon provider became the first dentist in the United States to give a COVID-19 vaccine, and in early January 2021, California approved a public health emergency waiver authorizing dentists to vaccinate against COVID-19. In South Carolina, some ambulance agencies are training paramedics to administer the vaccine, and expect that they may eventually go directly to people’s homes to vaccinate them , and in Illinois, the director of the Department of Public Health modified EMT’s scope of practice to allow advanced and intermediate EMTs to vaccinate.

State officials hope that expanding providers’ capacity to administer vaccines might help reach more individuals faster, especially as states expand priority phases to include more people. According to Claire Hannan, executive director of the Association of Immunization Managers, staffing is one of states’ greatest needs. Expanding scope-of-practice laws is one way to increase staffing, but Hannan suggests that states might also consider using new federal money to onboard more staff — both those who can physically administer the vaccine and those who can help with data entry, provider enrollment, and vaccine ordering.

Establishing accessible vaccination venues: As states move into new distribution phases, processes will change, shifting from closed to open points of distribution. Many states are planning to open mass vaccination clinics to help distribute the vaccine more rapidly to residents. Over 50,000 people in Pennsylvania have already registered for the vaccine, and one Pennsylvania clinic reported having 2,600 doses and plans to inoculate three to seven people every five minutes. New Jersey announced the sites of six mass vaccination clinics across the state, which include two malls, two convention centers, a stadium, and one college facility; and as of Jan. 18, 2021, some of them had begun vaccinating people in eligible phases.

In Oregon, four health systems are joining forces by pooling their COVID-19 vaccines and staff to run a clinic at the Oregon Convention Center to serve eligible residents starting Jan. 23, 2021, which will include people over age 65 and teachers. Montana plans to use federal money from the new stimulus package to finance mass vaccination clinics run by community health centers and local health departments. To staff these clinics, many states are using the National Guard and local health care workers, with some also tapping EMTs for the job.

So far, states that have already started operating mass clinics have found them to be effective at vaccinating large numbers of individuals in a small amount of time. Arizona began vaccinating people at State Farm Stadium, which has been so successful that the state announced they are opening additional sites beginning Feb. 1, 2021, with appointment registration beginning this week. Additionally, a vaccination clinic operating at the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta was able to vaccinate over 4,000 people in its first week of distribution.

States and counties running these mass clinics are using different mechanisms to track vaccine administration and monitor individuals for any adverse reactions immediately after vaccination. In Oregon, members of the National Guard are helping run the clinics, including assisting with traffic control, processing electronic medical records data, monitoring individuals after vaccination, and even administering vaccines. Clark County, Wisconsin officials asked that anyone coming to their drive-through vaccination clinic complete a COVID-19 Vaccine Administration Record beforehand, which includes demographic and medical history information that is then shared with the Wisconsin Immunization Registry. Clark County also has EMTs on site to help monitor individuals after vaccination.

The New Jersey Convention Center, which will be the site of up to 2,400 doses per day, has 100 staffers on site – including health care workers and National Guard members – to provide registration and security services, administer the vaccine, and monitor individuals post-vaccination.

Mass vaccination clinics are promising. Questions remain, such as how to operate them efficiently and:

- Avoid reported long lines and staffing issues, while also following COVID-19 safety and distancing protocols;

- Ensure equal access for everyone who wants to get vaccinated; and

- Address concerns of those who may feel more comfortable getting vaccinated in familiar, community settings with trusted providers who can answer any of their questions and ease anxiety about the process.

Deploying leftover doses: Due to the short shelf life of the vaccine and the number of people choosing to delay getting it, vaccine administrators are often faced with the challenging situation of finding individuals to vaccinate before the doses expire. States are working to ensure that leftover doses are not wasted. New York health care providers now must use their total vaccine allocation within a week or face a penalty. Florida also announced hospitals would face fines for not using their total allotment of vaccines, and the state deployed an additional 1,000 nurses to aid in administering vaccines and help keep clinics open seven days a week to ensure doses do not go unadministered. Other states, including Connecticut, have released guidance policies to prevent wasted vaccinations. According to the Connecticut Department of Health guidance, vaccine providers should keep a wait list of people to call in case they have extra doses.

These state tactics show that having an enforceable plan is critical to ensure doses are provided to priority patients and not wasted.

Looking Forward

Through previous CARES Act funding, HHS distributed $200 million across 64 states and jurisdictions for vaccine planning and preparedness. Though originally earmarked to be spent by Dec. 31, 2020, HR 133 extended the deadline for states to spend down their CARES Act funding for an additional year, sunsetting at the same time as HR 133. State officials had noted that this funding was insufficient for adequate vaccine planning and distribution.

The omnibus bill (HR 133) signed into law on Dec. 27, 2020, includes $8.75 billion in funding for states’ vaccine distribution with a spending deadline of Dec. 31, 2021. These funds will be distributed to federal, state, local, territorial, and tribal public health agencies to “administer, monitor, and track coronavirus vaccinations to ensure broad-based distribution, access, and vaccine coverage.” In this fund, $300 million has been earmarked for distribution and administration of vaccines in high-risk and underserved populations, including populations of color and rural populations. The new funds will be available to states within 21 days, but many are concerned that it is too late to fully support the staffing required in the roll out.

An additional $3 billion is available to states through the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act to support state’s COVID-19 vaccination activities through an existing CDC Immunization cooperative agreement. States are identifying what the money will be used for specifically.

Last week, President-Elect Joseph Biden announced a $20 billion national program to establish community vaccination centers across the country, including mobile units in more rural and remote communities and mass vaccination clinics. This plan must be approved by Congress, but demonstrates his priorities of comprehensive coverage and equitable distribution. As states await action on Biden’s proposal, their efforts to launch mass vaccination clinics can inform federal policy and establish an infrastructure for speedy deployment as more vaccine becomes available. Similarly, states can report on the challenges experienced with the chain store program and how they were remedied in order to ensure the problems are not repeated.

*As of 8 p.m. Jan. 18, 2020.

This analysis is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award totaling $200,000 with 100 percent funded by CDC/HHS. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by CDC/HHS or the US government. CDC General Terms and Conditions for Non-research Awards, Revised: January 2021.