Family caregivers help Medicaid enrollees safely stay in their own homes, prevent or delay hospital and nursing facility stays, and provide personal care services that Medicaid agencies would otherwise need to pay for. However, there are strong indications that family caregivers need additional supports, which would benefit the Medicaid enrollees in their care. Recognizing family caregivers’ critical contributions, state Medicaid agencies already provide training, services, or, sometimes payment to them. This report examines the strategies states currently use and presents four interrelated actions the federal government could take to foster spread of innovative strategies that some states have developed.

Family caregivers help Medicaid enrollees safely stay in their own homes, prevent or delay hospital and nursing facility stays, and provide personal care services that Medicaid agencies would otherwise need to pay for. However, there are strong indications that family caregivers need additional supports, which would benefit the Medicaid enrollees in their care. Recognizing family caregivers’ critical contributions, state Medicaid agencies already provide training, services, or, sometimes payment to them. This report examines the strategies states currently use and presents four interrelated actions the federal government could take to foster spread of innovative strategies that some states have developed.

Executive Summary

Most individuals with long-term care needs prefer to remain in their homes and communities rather than enter an institution. Family caregivers play an important role in states’ efforts to help Medicaid enrollees safely fulfill that preference. Their contributions also help offset the cost of personal care services and can delay the need for more costly services, such as hospital and nursing facility services. Recognizing their importance, state Medicaid agencies already support family caregivers through training, services, or, sometimes payment. However, there are strong indications that family caregivers could benefit from additional supports, especially those targeted to meet caregivers’ specific needs. These supports would, in turn, benefit the Medicaid enrollees receiving their care.

Some states have already implemented innovative strategies that address critical issues in family caregiver support. The following are among the many examples discussed in this report.

- Colorado, in some circumstances, waives scope of practice laws to enable family caregivers to be paid to provide skilled health-related activities.

- In Florida, the managed care organization (MCO) that serves children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN) provides behavioral health services for family caregivers as a value-added service.

- Georgia has established a mechanism to identify and deliver individualized training to family caregivers that is based on information collected through the care coordination process.

- Tennessee requires its MCOs to conduct formal caregiver assessments and plan to meet needs identified in the assessment.

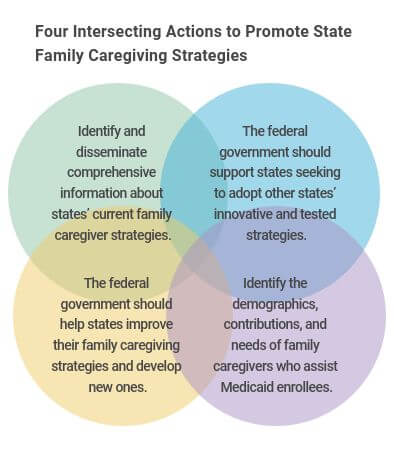

An examination of state strategies, research, and input from state officials identified four interdependent actions that the federal government could take to improve family caregiving as part of the national strategy.

- Foster the spread of innovative family caregiver support strategies already tested by leading states.

- Support the efforts of states to continue to advance their existing innovations and develop new ones.

- Conduct a comprehensive, systematic effort to identify and disseminate information about states’ innovative and tested family caregiver strategies that would help other states choose and implement the strategies that would work best for them, especially in the areas of cost and effectiveness.

- Measure and evaluate the number, demographics, contribution, needs, and priorities of the family caregivers who assist Medicaid enrollees.

When considering these actions, it is important to consider that the current pandemic and its impact on state budgets will, at least temporarily, make it difficult for states to contemplate implementing any new policies, especially those that require upfront investments. COVID-19 is, however, taking its greatest toll on nursing facility residents[1] and members of low-income and minority populations.[2] Supporting family caregivers in their efforts to help their loved ones remain in their own homes could help mitigate the impact of the infection. The pandemic also creates a window of opportunity that both federal and state policymakers could use to prepare for future action.

Introduction

The relatives and friends who provide hours of often unpaid care to help their loved ones with their self-care needs are linchpins in states’ long-term services and supports (LTSS) systems. These family caregivers, who are often members of the Medicaid enrollee’s own community and likely to speak the enrollee’s preferred language, provide companionship, help with household chores, and assistance in medical care. This support, in turn, helps children with special health care needs, adults with disabilities, and older adults remain in their own homes rather than enter institutions. Caregiver support also can prevent costly hospitalizations and other adverse medical events.

Medicaid, and Medicaid-financed LTSS, are major costs to states. Medicaid accounted for 28.9 percent of all state expenditures in fiscal year (FY) 2019[3] and in FY 2017, more than 20 percent of all Medicaid spending was for LTSS.[4] Medicaid is also the major payer for LTSS in the United States. In 2018, the program paid over half of all LTSS spending – almost $197 billion – including about $92 billion on home- and community-based services (HCBS).[5] As a result, Medicaid reaps substantial benefits from family caregivers’ contributions and could benefit from helping these individuals better meet the needs of their loved ones over the long term. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) provides compelling evidence for the benefits that better family caregiver support could offer to the caregiver, care receiver, and payer:

…several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that when older adults’ caregivers receive a standard assessment, training, respite, and other supports, caregiver outcomes improve. In addition, older adults’ nursing home placement is delayed, they have fewer hospital readmissions, decreased expenditures for emergency room visits, and decreased Medicaid utilization.[6]

To better support family caregivers, Congress passed the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage Family Caregivers Act of 2017 (RAISE Family Caregivers Act), which established the Family Caregiving Advisory Council. In the legislation, the advisory council, along with the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, was tasked with producing and maintaining a national Family Caregiver Strategy that identifies “recommended actions that federal (under existing federal programs), state, and local governments, communities, health care providers, long-term services and supports providers, and others are taking, or may take, to recognize and support family caregivers.”[7] One part of this strategy will be an assessment of how family caregiving impacts the Medicaid program and the role Medicaid plays (and could play) in supporting family caregivers. This report provides that assessment, which will be presented in the council’s initial report to Congress, that in turn will form the basis of the national family caregiving strategy.

This report is designed to both inform the national family caregiving strategy and help state officials weigh options to better support family caregivers. Both goals are met through an examination of promising practices that some states have already implemented. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on state budgets may make it difficult for states to implement new policies that have upfront costs for some time, even if the investment is expected to generate longer-term savings. However, not all of these innovations require upfront investments, and some costs may be almost immediately offset by reductions in other services (e.g., replacing a minimum number of hours of paid personal services with a stipend to a family caregiver). Even if states can’t make immediate investments to help family caregivers improve their ability to care for their loved ones, the potential benefits of these initiatives will remain after the economy recovers. Additionally, the federal government could use the delay to prepare to support states and state officials can use the time to consider their options.

Report Development Process

The actions for federal consideration presented in this report were developed by the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), based on the organization’s previous work on these issues and with significant state research, guidance, and input. NASHP, with the support of The John A. Hartford Foundation, created the RAISE Act Family Caregiver Resource and Dissemination Center to support the Advisory council and its work. The information in this resource center, including advisory council meeting material and notes, as well as reports, was the starting point for developing this report. NASHP staff reviewed this information to identify information gaps, an initial set of key issues, and promising practices in use by one or more Medicaid agencies. This information was augmented by review of other relevant literature and state websites. All states highlighted in the report were offered an opportunity to review the information presented about their policies and provide input on all other aspects of the paper. The authors also held individual report review meetings, via telephone, with representatives of three states who serve as faculty to the advisory council. Finally, a draft of the report was reviewed by members of NASHP’s long-term and chronic care steering committee and its state leadership council on palliative care.

Background: Family Caregiving and its Effect on Medicaid

Family caregivers include “all who are caring for individuals across the life span with chronic or other health conditions, disabilities, or functional limitations.” The support may include help with feeding, bathing or toileting (i.e., Activities of Daily Living or ADLs) or help with shopping, cooking or handling finances (i.e., Instrumental Activities of Daily Living or IADLs).

Caregivers’ contributions lessen the need for home health and help prevent unnecessary hospitalizations or nursing facility stays.[8] One study, which focused on adults with LTSS needs, estimated that, the “economic value of family caregiving was $470 billion in 2017, based on about 41 million caregivers providing an average of 16 hours of care per week, at an average value of $13.81 per hour.”[9]

What do caregivers contribute?

- One study of adults with LTSS needs, estimated the value of family caregiving was $470 billion in 2017, based on 41 million caregivers providing 16 hours of care weekly.

- Another study of CYSHCNs caregivers estimated they provided 1.5 billion hours of care to 5.6 million children worth between $11.6 and $35.7 billion.

Another study examining the contributions of children’s caregivers estimated that each year these caregivers provide 1.5 billion hours of care to about 5.6 million children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN) with an estimated economic value of between $11.6 and $35.7 billion.[10]

No nationwide family caregiver statistics are available showing the economic value that family caregivers provide to Medicaid. Little is known about the needs and priorities of the family caregivers who serve Medicaid enrollees or the cost and effectiveness of the support strategies that states have already implemented. However, available information indicates that family caregivers make significant contributions to state Medicaid programs and that providing more support to family caregivers would benefit the Medicaid enrollees for whom they care, the caregivers themselves, and the Medicaid program.

Given that the cost of Medicaid LTSS is substantial — $196.9 billion in 2018[11] — and that Medicaid pays for over 50 percent of all LTSS costs,[12] it is expected that family caregivers play an important role in the delivery of these services. This is especially true for the millions of individuals participating in HCBS programs[13] – who all need assistance to perform some ADL or IADLs – because it is often the family caregivers’ contributions that prevent the need for institutional and other services, including hospitalizations and home health aide services.

In addition, family caregivers help Medicaid agencies deliver care that respects enrollees’ cultural and language preferences. Most family caregivers understand the care receivers’ cultural preferences and typically speak the individual’s preferred language. Because family caregivers are often members of the Medicaid enrollee’s own community, they are well-suited to helping enrollees maintain the community ties they value.

Finally, family caregivers are critical to Medicaid agencies’ decades-long effort to eliminate institutional bias by increasing access to non-institutional services (i.e., balance the long-term care system). This bias resulted from federal Medicaid rules that require states to cover nursing facility services, but not HCBS. As a result, Medicaid spending on institutional care was much greater than its spending on HCBS — in 1981, HCBS made up just 1 percent of all LTSS spending and it wasn’t until 2013 that Medicaid agencies first began spending more on HCBS than institutional care.[14] Despite this progress, in FY 2018, 41 states reported that there was a waiting list for at least one of their HCBS programs, indicating that unmet need for non-institutional services remains.

CMS describes a balanced LTSS system as:

“.. a person-driven, long-term support system that offers people with disabilities and chronic conditions choice, control and access to services that help them achieve independence, good health and quality of life.’

States are seeking to rebalance the system because most people prefer to stay in their own homes.[15] Also, due to the Supreme Court’s 1999 ruling in the Olmstead Case that “unjustified segregation of persons with disabilities constitutes discrimination in violation of Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act.”[16] The federal government has supported states’ efforts to respond to this ruling with its strong direction to make HCBS more available. Supports included guidance through a series of Medicaid Director letters, legislation creating new pathways for HCBS coverage (described later in this report), and state funding opportunities. The contributions of family caregivers are critical to these efforts because, as previously discussed, it is often the family caregivers’ assistance that enables individuals with LTSS needs to remain in their communities.

Family caregivers’ contributions to Medicaid’s LTSS system are clearly valuable. But most Medicaid agencies’ caregiver supports are designed to help those who have taken on new tasks and there are strong indications that caregivers would benefit from skill building. There are also indications that caregivers would benefit from other supports that would give them a break from caregiving. For example, some studies have found high rates of avoidable hospitalizations among HCBS program participants with both Medicaid and Medicare coverage (the dually eligible). One of these studies did not provide comparative nursing facility information and may not be generalizable to other groups who are participating in HCBS.[17] However, another study did find that dually eligible HCBS program participants with dementia had higher rates of hospitalization than those in a nursing facility. This difference was even more pronounced among Black Americans. This study found that caring for a person with dementia can be more stressful than caring for others and, “the presence of dementia may exacerbate caregiver burden such that outcomes for the care recipient suffer.[18] In addition, the National Academies have documented the toll that caregiving can take on caregivers’ health, well-being, relationships, and economic security. Taken together, these studies indicate that alleviating caregiver burden, especially among those caring for Medicaid enrollees with dementia, could lead to improved care for enrollees and, perhaps, reduce family caregiver burnout. Also, helping family caregivers improve their skills, especially those that could prevent avoidable hospitalizations, would benefit Medicaid enrollees and the agencies themselves.

Primer: Medicaid and Family Caregiver Support

The innovations and actions presented in this report are enhanced by an understanding of the Medicaid program’s strictures and flexibilities, especially as they apply to family caregiver support.

Introduction to Medicaid

Medicaid provides coverage to millions of people, in October 2019 the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reported the program covered over 64 million individuals.[19] Medicaid serves low-income families and children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, and older adults. The program is a partnership between federal and state governments, meaning that states establish program policies according to federal rules and share program costs with the federal government.

States document their policy choices in their Medicaid state plans. These plans describe which types of services the state will cover, which people the program will cover, what qualifications providers must meet, and how much they will be paid. States obtain approval for changes to these policies by submitting a state plan amendment (SPA) to CMS, which is the federal agency that administers the program. If a state wishes to implement a program policy that does not meet standard federal rules, such as covering a service that is not a standard benefit or limiting the number of enrollees who may receive a service, it must obtain CMS approval of a waiver of that rule. There are several types of waivers, which offer varying types of flexibility to states. Collectively, waivers, state plans and SPAs are referred to as federal authorities. The federal authorities that states use to provide LTSS, including caregiver supports, are described here in order of the flexibilities they offer states (least to most).

State Plan Services

Among LTSS, federal rules require states to cover nursing facility and home health services in their state plans (making them mandatory benefits). States may also choose to cover several optional LTSS benefits in their plans, including personal care, services in an intermediate care facility for individuals with intellectual disability (ICF/ID), and inpatient psychiatric services for individuals under age 21. Services provided under a state plan must be available to Medicaid enrollees across the state in the same amount, scope, and duration. Enrollees must also be able to choose the Medicaid-enrolled provider for their care. Also, under the mandatory Early and Periodic, Screening Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, states must provide all services that can be covered under federal Medicaid law that are needed to correct or ameliorate a child’s physical, developmental, or mental condition(s). In no case can a state cover a service provided by someone who is not covered by the program, such as a family caregiver who is not also a Medicaid enrollee. The state may cover benefits, such as respite care, that are provided to the enrollee but also support the caregiver.

As previously mentioned, states also use their state plans to document which individuals they will cover. There are both mandatory and optional eligibility groups. Mandatory groups include a few who are likely to need LTSS, such as individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Most people who receive LTSS, such as individuals eligible for HCBS under institutional rules, are, however, members of optional eligibility groups. Many people qualify for Medicaid based solely on their income. These people may qualify to receive LTSS based only on their functional need. For example, their need for assistance with ADLs or IADLs must be sufficient to meet a state standard, which is usually set at the level needed to qualify for institutional care, such as that provided by a nursing facility. Many states have also chosen to cover some people who need LTSS whose income would otherwise be too high to qualify for Medicaid. These people must meet both financial and functional criteria to qualify for Medicaid. Family caregivers are not a group that states may choose to cover under their state plan.

In recent years, Congress has enacted legislation that offers states greater ability to cover HCBS under a state plan. States may now choose to offer the following coverage by obtaining CMS approval of an SPA. (Note that under these provisions, states may not cover family caregivers nor may they provide services to family caregivers.)

Section 1915(i) of the Social Security Act was enacted as part of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA) and amended by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA). Under this provision, states can elect to provide HCBS to older adults and individuals with disabilities by submitting an SPA. Eligibility for the services is determined based on functional and financial criteria. Medicaid enrollees with incomes up to 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) who meet functional criteria set by the state may receive the HCBS. States may also opt to extend the services to individuals with higher incomes, if they would qualify for one of the state’s HCBS waivers (i.e., qualify for care in an institution, such as a nursing facility, hospital or ICF/ID). States may choose to allow enrollees to self-direct services, enabling enrollees to hire a caregiver of their choice, including a family caregiver, to provide their Medicaid-covered services. States may target this service to subgroups of enrollees based on age, disability, diagnosis, and/or eligibility group, but if they choose to do so they will need to seek a renewal of their SPAs every five years. States may not limit the number of enrollees they will serve under this provision nor may they limit program availability based on geography. As of August 2020, 19 states had a current 1915(i) SPA. (Three had SPAs that were no longer in effect.)[20]

Section 1915(j) of the act was enacted as part of the DRA. Under this provision states can elect to allow enrollees to self-direct the personal assistance services for which they qualify by obtaining approval of an SPA. As previously indicated, self-direction enables enrollees to use Medicaid funding to pay family caregivers for providing personal assistance services. Through the SPA, states establish policies about whom the Medicaid enrollee may hire, including whether or not the enrollee may hire legally responsible relatives. States can limit the number of enrollees who can choose to self-direct and can limit program availability to part of the state. As of May 2017, eight states had a 1915(j) SPA.[21]

COVID 19 and Family Caregiving under Medicaid

States have taken action to support enrollees and their caregivers, including family caregivers, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most often, states have used Appendix K amendments, which were created to speed response to national disasters, to modify their 1915(c) home- and community-based services waivers to incorporate flexibilities that can support family caregivers, such as flexibilities on home-delivered meal services or allowing family caregivers to receive reimbursement for providing specified services. As of August 2020, almost all states and Washington, DC have submitted at least one Appendix K application to amend a waiver. Information about states that have submitted Appendix K amendments is available at Medicaid.gov.

- At least one state (Georgia) has used Section 1135 waiver authority, which allows waivers of federal Medicare, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program rules in a public health emergency, to temporarily allow payment for personal care services provided by legally responsible individuals, including legally responsible family caregivers.

- Six states have submitted COVID-19-related 1115 waiver requests, including North Carolina’s request for waivers to allow expedited LTSS eligibility.

Source: CMS

Section 1915(k) of the act (i.e., Community First Choice or CFC) was enacted as part of the ACA. Under this provision states may elect to provide personal care and a limited package of associated services to most Medicaid enrollees who require an institutional level of care by obtaining approval of a SPA. States may allow self-direction of these services. To incent uptake the federal government offered to pay a greater share of the cost of providing CFC services than other services. As of August 2020, nine states had an active 1915(k) SPA.[22]

Waivers

States primarily use two types of waivers to provide LTSS. A 1915(c) waiver allows the provision of HCBS while 1115 waivers allow the waiver of almost all federal Medicaid rules under certain circumstances. An 1115 waiver is the only federal authority under which a state Medicaid program can currently cover or provide services to family caregivers who do not otherwise qualify for Medicaid. Unlike SPAs, waivers are approved for a defined period of time after which states must secure approval of a new waiver or revert program policies back to standard Medicaid rules.

Section 1915(c) of the act was enacted in 1983. A 1915(c) waiver enables states to offer HCBS services as an alternative to institutional care. As of August 2020, 47 states and Washington, DC were operating almost 300 HCBS programs under approved 1915(c) waivers.[23] States can target these waivers to any group of enrollees who meet the state’s criteria to receive institutional care (e.g., adults with physical disabilities or children with autism). States may also:

- Limit the number of enrollees who may participate in the program;

- Limit the program to certain parts of the state;

- Cover people in the community who meet the financial standard to qualify for institutional care; and

- Offer a range of HCBS benefits, including services provided to the enrollee that also support family caregivers.

Among other requirements, states must demonstrate that the cost of providing services under the waiver will be no more than the cost of providing institutional services and ensure that the services are provided under a person-centered plan of care. Waivers are granted for no more than five years.

Section 1115 of the act has been part of the Medicaid program since its creation in 1965. These Research and Demonstration Waivers can, with the approval of the HHS Secretary, be used to waive almost any federal Medicaid rule, including those that restrict the provision of services to family caregivers. These waivers must be designed to allow research and demonstration projects (including statewide projects) and “promote the objectives of the Medicaid program.” They must also be budget-neutral, meaning that the cost to the federal government of serving enrollees under the waiver must be no more than what the cost would have been without the waiver. These 1115 waivers are usually approved for an initial five-year period followed by three- to five-year renewals. In FY 2018, three states (Arizona, Rhode Island, and Vermont) delivered HCBS services solely under an 1115 waiver. Another nine states delivered HCBS services under both 1115 and 1915(c) waivers.[24]

Medicaid Managed Care Opportunities

In 2019, 36 states enrolled at least some Medicaid enrollees with disabilities and older adults into Medicaid managed care programs—and 26 states enrolled more than half of the members of these populations into MCOs.[25] In these programs, the state Medicaid agency contracts with a managed care organization (MCO) or other managed care entity to deliver a specified package of benefits to enrolled enrollees. In 2019, 23 states operated managed LTSS (MLTSS) programs through which the state delivered LTSS services through MCOs to one or more groups of enrollees.[26]

Managed care offers three additional opportunities to support family caregivers. States establish performance expectations in the contracts they sign with MCOs and other managed care entities, including expectations that support family caregivers. As will be discussed in the Innovations section, Tennessee, for example, requires MCOs to formally assess caregiver needs as part of each enrollee’s care planning process. Florida requires its MCO that serves children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN) to provide training to family caregivers which will enable them to better care for their children with special health care needs. MCOs and other types of managed care entities can also, with the approval of the state, offer their members services or settings in-lieu-of one covered by a state plan. The cost of these services is usually considered in MCO payments. Finally, MCOs and other types of managed care entities can also voluntarily provide value-added services to their enrollees. Value-added services are services that are not in the state plan. Florida’s MCO for CYSHCN offers value-added benefits that support caregivers, including benefits counseling and behavioral health counseling. The cost of value-added services is not considered in MCO payments.

Addressing Medicaid Enrollees’ Social Determinants of Health Needs

In recent years, both the federal and state governments have recognized the importance of addressing the social determinants of health (SDOH) to improve overall health. It is now broadly accepted that clinical care alone may not produce health outcomes. Factors such as food and housing insecurity have major influences on health outcomes.[27] In light of this, some states have, with CMS support, been developing pathways to address some SDOH needs of Medicaid participants. Many of these result from the flexibilities offered by Medicaid managed care. Others rely on waivers and SPAs. While a family caregiver is not the same as an SDOH, they like an SDOH have a major impact on Medicaid enrollees’ health and well-being. Therefore, the paradigm shift that led to state and federal government action to address SDOH for Medicaid participants may lay the groundwork for a similar shift that not only recognizes the needs of family caregivers but meets more of those needs.

Introduction to Family Caregiver Support in Medicaid

It is important to understand the basics of family caregiving in Medicaid when considering the innovations and recommendations presented in this report. This section provides that information and details who can receive and who can deliver family caregiving, as well as introductory information about the types of supports that Medicaid currently provides to family caregivers.

Children and Family Caregiving Across the Lifespan

This report explores issues in family caregiver support across the lifespan, but there are several important differences between family caregiving to children and to adults, including:

- Determining children’s functional eligibility for HCBS, which is often a major entry point for family caregiver support, is complicated by the parent’s expected role. Functional eligibility is traditionally tied to the need for assistance with ADLs or IADLs like bathing, dressing, and cooking — activities that parents are expected to assist their children in completing.

- Children are expected to be able to act more independently as they grow older. While states have noted the benefit of leveraging a universal assessment across HCBS programs, children may benefit from an assessment that is tailored to identify their age-specific needs.

- Many states, due to program integrity concerns, have established policies that prevent payment to legally responsible caregivers (parents and legal guardians) under a self-directed HCBS option. While these concerns are real, they need to be balanced with the potential impact of that lack of payment on the caregiver parent.

Source: Honsberger, K, et al. State Approaches to Reimbursing Family Caregivers for Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs through Medicaid. NASHP, report forthcoming.

Whom Do Family Caregivers Serve?

Eligible older adults, children, and adults with physical, intellectual, developmental, or cognitive disabilities can receive services through Medicaid, along with people with behavioral health needs. Family caregivers serve members of all of these groups. Family caregivers care for those who reside in institutions as well as those who live in the community. Also, the family caregiving role can begin before the enrollee becomes functionally eligible for institutional care (i.e., meets institutional level of care requirements), which is the point at which the enrollee qualifies for both institutional and HCBS services. Unfortunately, little is known about the demographics, health conditions, or functional status of the group of enrollees who are served by family caregivers. However, the information presented here, while not specific to this group, does provide some insight into its probable make-up.

CYSHCN, adults with disabilities, and older adults are most likely to need the support of family caregivers. In FY 2015, an estimated 8 percent of approximately 70 million Medicaid enrollees were ages 65 and older, and 15 percent were people with disabilities under the age of 65.[28] Further, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) estimates that in 2013, approximately 600,000 dual-eligible (those covered by both Medicaid and Medicare) used HCBS waiver services, and about 400,000 used HCBS State Plan services.[29] In 2017, 47 percent of 13.3 million CYSHCN were covered through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).[30]

Medicaid enrollees participating in HCBS programs are most likely to rely heavily on family caregivers to augment the services provided by their Medicaid program. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation,[31] in FY 2018 about 2.3 million enrollees received HCBS under a state plan (home health and/or personal care services). About 2.5 million did so under a waiver — with 1.8 million receiving HCBS under a 1915(c) waiver.[32] Information about the national number of individuals in different populations receiving HCBS through waivers or state plans is limited, although one study estimated about 630,000 individuals with I/DD were served on 1915(c) waivers in FY 2015.[33]

Who Are Family Caregivers?

The term ‘family caregivers’ is used to convey the difference between informal or “family” caregivers and those who are caregivers by profession. In other words, family caregivers are not just immediate relatives but also the neighbors, friends, and others who provide care. There is also a dearth of information about Medicaid enrollees’ family caregivers in terms of demographics, contributions, and needs, distinct from those of other family caregivers. It is expected that as the characteristics of Medicaid enrollees vary from that of the US population as a whole, the characteristics of their family caregivers will similarly vary. Also, Medicaid is designed to serve poor or low-income people and, as a result this population has fewer resources than others to dedicate to their own care. (This income difference probably holds true even for those who qualify for HCBS services, which often allow people with higher incomes to enroll into Medicaid.) The relative lack of financial resources may result in a higher caregiver burden, and perhaps different priority needs, for the family caregivers of Medicaid enrollees than caregivers as a whole.

A 2014 snapshot of family caregivers to Medicaid enrollees in Texas found:

- 19% were spouses;

- 47% were their children;

- 10% were other relatives; and

- 12% were grandchildren, grandparents, life partners, or siblings.

- 97% were unpaid.

During report production authors identified one state (Texas) that had collected information on family caregivers from applications submitted to three community services programs. Only one of these programs was Medicaid-funded, but all incorporated income limits, thus the report’s findings begin to reveal the demographics and needs of Medicaid enrollees’ caregivers in one state. In 2014, this assessment of informal caregivers found that 19 percent of respondents were spouses, 47 percent were children of the care recipient, 10 percent were other relatives, and 12 percent were grandchildren, grandparents, life partners or siblings of the care recipient, with 97 percent reporting they were not paid to provide care. Additionally, 38 percent of responding caregivers were self-reported as Hispanic, 26 percent were non-Hispanic White, and 25 percent were Black/African American. Also, 84 percent of informal caregivers were of working age (between the ages of 18 and 64).[34]

Supports Medicaid Provides to Family Caregivers

States have long recognized the importance of supporting family caregivers and all provide some type and amount of support. The major types of support that states currently offer include services that serve both the enrollee and the caregiver, including payment, training and education, and care coordination.

Services for the enrollee that also support the caregiver. All states must provide home health services in their state plans. These services, although provided to the enrollee, also support the family caregiver. Other similar types of services that at least some Medicaid programs provide include home health aide services, home modifications, transportation, home-delivered meals, and adult day care. Some Medicaid HCBS programs also cover respite support for care recipients, which can give relief to family caregivers. Respite refers to providing short-term care in order to allow a primary caregiver to have a break from caregiving. One study found that, in 2015, 47 states and Washington, DC provided some form of caregiver support or respite in state plan or waiver programs for older adults and people with physical disabilities.[35] Also, a 2019 article analyzing 1915(c) waivers that included children with complex medical needs found that, across 142 waivers in 45 states, 81 percent of waivers (115) covered respite care.[36]

Payment. All 50 states and Washington, DC have at least one Medicaid self-direction option.26 Self-direction enables enrollees to use Medicaid funding to pay for aides of their choice, including family caregivers, to provide personal assistance services. Further, states can define which family caregivers can be paid under the self-directed option. Representatives who direct the services that enrollees receive may not also receive payment for providing care, and in some states, family caregivers cannot live in the same home as the care recipient and receive payment. States may place other restrictions on this flexibility. Additionally, states have reported considerations about flexibilities in family caregivers’ ability to receive payment due to concerns about replacing enrollees’ natural caregiver support.[37]

Training and education. Training supports can be targeted toward helping family caregivers of specific populations — for example, supporting training and education for caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias, or caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities. Education and training could also include training on helping caregivers assist care recipients with functional needs. According to a NASHP scan,[38] as of March 2020, approximately half of states provided some form of education, training, or counseling support through a Medicaid waiver or SPA, targeted toward family caregivers of older adults and people with functional limitations. Another study that analyzed 88 I/DD waivers from 41 states and Washington, DC, reported 29 waivers (about 33 percent) offered some form of family or caregiver training.[39] A 2016 review of waivers for children with autism found that 10 waivers specifically targeting children with autism included support for caregiver training.[40]

Care coordination. Medicaid programs can also cover care coordination services. These services, often provided through a person-centered plan of care based on a formal assessment of the enrollee’s needs and goals, can seek to coordinate different LTSS, other Medicaid-covered services, and social services. This support relieves caregiver burden. According to Kaiser Family Foundation,26 in FY 2018, seven states offering 1915(i) state plan services reported offering case management services (two states reported I/DD target populations, two states reported seniors and/or people with physical disabilities target populations, and three states reported mental illness target populations), though this data was limited by the small number of states responding. Also, a 2013 AARP report found that approximately 30 percent of states included some form of family caregiver assessment in their Medicaid HCBS waiver assessment processes.[41] These states have begun to build an infrastructure that would enable them to consider caregiver needs in enrollee care planning.

How the Federal Government Promotes State HCBS Innovations

The federal government has offered funding to states to incentivize and support implementation of new strategies that shift care toward HCBS. Two programs offer examples of two different funding mechanisms.

Balancing Incentive Program (BIP). BIP was created by the Affordable Care Act and ran from 2011 to 2015. It provided funding to states by temporarily increasing the federal share of the cost of providing LTSS (increasing the Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentages, or FMAP, for the services). It targeted states with a strong bias toward institutional services in their Medicaid programs. Only states that were spending more than half of their LTSS funding on institutional services were eligible to participate. Participating states committed to increasing non-institutional LTSS spending in order to receive the FMAP increase. For example, states spending 25 to 50 percent on non-institutional LTSS agreed to increase non-institutional LTSS spending to 50 percent by September 2015 in order to receive a 2 percent increase in FMAP for specified non-institutional LTSS provided during the term of the program. Participating states also committed to implementing No-Wrong-Door systems to increase access to information on Medicaid LTSS, core standardized assessments, and conflict-free case management. States used the funding to pay for new or expanded noninstitutional services. They also received technical assistance from contractors and CMS staff. According to an ASPE evaluation, the majority of the 18 participating states met goals for increasing the proportion of HCBS spending and developing infrastructure.

Real Choice Systems Change Grant Program. Beginning in 2001, the Real Choice Systems Change grant program was designed to support states in shifting LTSS spending towards HCBS through development of infrastructure. In 2001, CMS made noncompetitive $50,000 starter grants available to states, and initial grants averaged $300,000 to $800,000 over a three- to four-year period, targeting specific parts of states’ HCBS systems. Grantees were required to provide a 5 percent non-financial contribution to the total grant award. A shift occurred in 2005 toward awarding fewer grants for larger amounts in order to support overarching change. A synthesis of initial states’ experience shows that almost all grantees reported successfully implementing and sustaining their improvements. According to the synthesis, some grantees reported that they would have been unable to implement the improvements absent the grant funding and many noted that they were able to leverage this grant opportunity to implement additional reforms.[42]

Medicaid Innovations to Address Five Critical Family Caregiver Issues

Many state Medicaid agencies have already implemented strategies that support family caregivers, as highlighted in the Medicaid Primer section. Here are some of the more recent and less common strategies states have used to address five critical issues in family caregiving. These strategies were chosen to represent state efforts to support the family caregivers of a range of enrollees (e.g., from CYSHCN to older adults), implemented through different delivery systems (e.g., managed care and fee-for service), and by a diverse set of states (e.g., rural and urban). Other states have implemented innovations that address these and other issues and clearly states will continue to develop new innovations that address emerging issues. The critical issues and state innovations presented here should be considered first steps toward identifying promising practices in family caregiving — and not the final word about best practices that all should adopt.

Develop outreach to inform enrollees and caregivers about available caregiver supports.

Offering supports to family caregivers does little if enrollees and their families are unaware of the supports or don’t think they qualify for the assistance. State agencies and other organizations have already done a significant amount of work to inform enrollees and their families about available LTSS. For example, Aging and Disability Resource Centers provide information to family caregivers of all income levels in most states. But, the primary emphasis of this work is to support the individual who needs LTSS and the family’s role is often assumed to be that of helping their loved one obtain care.

Washington State’s outreach to family caregivers. Washington’s experience implementing its benefits for caregivers indicates that targeted outreach for family caregivers is often needed. When implementing its benefit for caregivers, Washington found that more individuals applied for the benefit than caregiver/care recipient dyads. They reported that one cause was that, “many informal caregivers do not think of themselves as caregivers until they become very stressed and, as a result, delay seeking these supports.” The state found it needed to conduct a broad-based awareness and outreach effort that included work with hospitals, employers, and community-based organizations. They also found benefit in partnering with local Area Agencies on Aging (AAA) to administer the outreach program. Many turn to AAAs in their local communities for help in obtaining LTSS, which gives the AAAs a natural link to family caregivers. These agencies have also contributed resources to the informing effort. Washington’s Pierce County, for example, developed a video to help family caregivers understand that help was available to them as well as their loved one. Much of the state’s effort was based on a campaign developed by the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation in Minnesota. This campaign was designed in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Human Services (which administers Medicaid[43]) and with replication in mind. The primary goal of the research-based campaign was to help caregivers recognize themselves as caregivers, a critical and often delayed first step to accessing caregiver services.

Train caregivers so that they can better meet the needs of their loved one.

As previously discussed, many states already offer training to caregivers, including family caregivers. Most training focuses on helping caregivers meet medical needs, such as training on how to use medical equipment, but some training focuses more directly on caregiver needs, such as coping skills.

Utah’s training to help caregivers deliver care. Utah’s New Choices 1915(c) waiver for adult enrollees living in institutions who wish to transition to a community setting covers training for unpaid family caregivers. The training is designed to enable caregivers to safely and effectively fulfill their responsibilities in delivering the services in enrollees’ care plans. It can include training on care regimens or the use of equipment. The training itself must be included in the care plan.[44] Similar family/caregiver training is also provided in Utah’s Community Supports and Community Transitions 1915(c) waivers that serve individuals with intellectual disabilities and other related conditions. This training may include behavioral support strategies in addition to navigating service delivery systems and support for self-administered services.

Georgia’s individualized training based in care coordination. Georgia’s Structured Family Caregiving program takes the concept of targeting caregiver training to enrollee medical needs one step further by offering individualized assistance (and a daily stipend) to unpaid family caregivers who live with a qualified 1915(c) elderly and disabled waiver participant. The individualized assistance features telephone and electronic support, including access to a secure electronic system for case management documentation (e.g., care plan notes) that is shared among the care team, including the family caregiver. The family caregiver has the support of other care team members, a health coach, and a registered nurse. According to the waiver request, family caregivers receive a minimum of eight hours of training each year that is targeted to individual needs identified through caregiver self-reporting, review of caregiver documentation, or case management activities. Training may be offered through a home visit, secure electronic communication, web-based training or other ways that are, “flexible, accessible and meaningful for the caregiver.”

Georgia’s Medicaid agency began offering this program in 2019 and estimated that in FY 2020 the cost of providing the service would be about $6.9 million ($2.2 million from the state). However, the state crafted the program so that its cost would be offset by a reduction in personal support services by setting the stipend rate at the equivalent of the cost of five hours of extended personal support services and then limiting program participation to waiver participants who need five or more hours of personal support services each day. The caregiver support is offered in lieu of the personal support, so the costs are certain to be equivalent [45]

Florida’s formal training delivered by MCOs. In 2013, Florida launched a managed LTSS (MLTSS) program that serves older adults and adults with disabilities who meet nursing facility level of care criteria.[46] The MCO contract for this program requires all MCOs to offer a formal family caregiver training program as a quality enhancement. The program must address “the financial, emotional, and physical elements of caregiving, as well as outline the resources available to caregivers in crisis.”[47] Contracted MCOs must maintain at least two training providers in each county it covers. Any MCO that fails to meet these requirements may be required to pay damages of $500/day. Florida Medicaid does not factor the cost of providing this training into MCO payment.

Identify and address relevant caregiver needs as part of care planning for the enrollee.

Existing federal Medicaid rules provide a starting point for caregiver assessment. As discussed in the AARP report, Family Caregivers and Managed Long-Term Services and Supports, caregiver assessments are required under 1915(i) and managed care regulations acknowledge the need in MLTSS. The example below illustrates how states can leverage MLTSS to identify and meet the needs of family caregivers.

Tennessee’s caregiver assessment and care planning. Since 2010, Tennessee’s Medicaid agency (TennCare) has contracted with MCOs to deliver LTSS through its CHOICES in Long-Term Services and Supports program (CHOICES). CHOICES serves adults with disabilities and those over age 65 who require LTSS. In its contract with MCOs, TennCare requires them to conduct a formal assessment of an enrollee’s caregiver and to include actions that address caregiver needs identified in the assessment within the plan of care developed for the enrollee. MCOs must assess the caregiver within 10 days of the enrollee’s referral to CHOICES and before completing the enrollee’s person-centered plan of care — and then at least once per year thereafter. Caregiver assessment may be conducted as part of enrollee assessment.

TennCare does not require that all MCOs use the same caregiver assessment tool. However, the agency does require each MCO to obtain approval for a standardized tool that the MCO will use in all assessments. TennCare’s contract also specifies the domains that the assessment must address. Required domains include:

- The family caregiver’s willingness and ability (e.g., employment status and other caregiving responsibilities) to serve effectively in that role;

- The caregiver’s health and well-being as it relates to the caregiver’s ability to support the person needing care;

- Caregiver stress due to providing care;

- Caregiver needs for training to assist the person needing care; and

- Service and support needs to better prepare the caregiver for their role.

Caregiver training and support needs identified in the caregiver assessment must be documented in the enrollee’s plan of care.

Offer services to help family caregivers.

Caregiving is a very stressful task, especially for family caregivers who often have other responsibilities, such as a holding a job or caring for other family members. This stress is intensified when the enrollee’s health, cognitive abilities, or ability to care for themselves decline. This stress can become so intense that caregivers become unable to reliably, effectively and safely perform their caregiving duties. If this occurs the enrollee’s health may suffer, the individual may need to be admitted to an institution, or the family caregiver may need to be replaced with a home health aide or other type of provider. Some states, such as the four profiled here, have found ways to offer family caregivers certain services that can help them manage the stress of caregiving, including connecting them to community resources that can help address their own potential needs for social services, such as housing assistance. As described below, Tennessee and Washington also use their 1115 waiver authority to extend these benefits to those at-risk of institutionalization.

Colorado’s coverage of family counseling for family caregivers. Since 2007, Colorado Medicaid has operated a 1915(c) palliative care waiver that serves children with life-limiting illness. The families that care for these children, who are unlikely to live long, are under extreme stress. Therefore, Colorado covers therapeutic life-limiting illness support, which includes family counseling services to “alleviate the feelings of devastation and loss related to a diagnosis and prognosis for a limited lifespan, surrounding the failing health status of the client, and the impending death of a child.” The intent of (and justification for) offering this service is to help the family, especially the caregiver, manage the stress that results from providing the intensive, daily care that a terminally ill child needs to, in turn, increase the likelihood that the child can continue to be cared for at home instead of in an institution. The counseling can be delivered by a licensed social worker, psychologist, and others. The provider can attend physician visits and hospital discharge meetings or connect the family with community resources. The family can receive up to 98 hours of therapeutic life-limiting illness support, every 365 days.

Florida’s requirement that an MCO provide behavioral health services for family caregivers. In 2016 Florida’s Children’s Medical Services (FCMS), which serves CYSHCN, began redesigning the program, which has operated for over 20 years. The goals of the redesign included enhancing care coordination and expanding benefits through a managed care contract (i.e., contract requirements and value-added benefits). The redesign was implemented in February 2019 when FCMS began providing statewide services through a single managed care contract (WellCare). Under the MCO’s contract it provides enhanced benefits to enrolled children that also support family caregivers, such as expanded non-medical transportation and housing assistance. The MCO also offers two value-added benefits that explicitly help family caregivers. As described on the program website, these are:

- Behavioral Health Services for Caregivers: Education and training for patient self-management by a qualified, non-physician health care professional using a standardized curriculum and 30-minute, face-to-face sessions with the patient/caregiver/family.

- Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Analysis for Non-Medicaid Caregivers: Including, health-focused clinical interview, behavioral observations, psychophysiological monitoring, health-oriented questionnaires, health and behavioral interviews. This counseling can be provided without the enrollee’s presence.[48]

Tennessee’s development of a family caregiver benefit based on caregiver input. During 2013 and 2014, TennCare conducted an extensive stakeholder input process to design a new HCBS program to better serve people with I/DD and their families. This process sought input from providers, advocacy groups, I/DD waiver participants and their families, and people on the waiting list to join the waivers and their families. The process sought input through individual interviews, statewide community meetings/discussion circles and a survey. When all of the input was analyzed, state officials unexpectedly found that the benefits that family caregivers reported they would find most helpful differed significantly from those that providers expected them to value. For example, HCBS providers thought that caregivers would benefit most from respite care, but waiver participants and their families reported that caregivers would benefit most from, “consistent, well-trained, quality staff,” and those on the waiting list asked for “personal assistance.” Both participant and waiting list respondents chose “family education/ navigation/support” as their second priority, but both groups also equally valued another type of service. The stakeholder process culminated in an amendment to the state’s 1115 waiver creating the Employment and Community First CHOICES (ECFC) program in 2016. (Note: This program structure is only currently possible through a 1115 waiver.)

Originally, the ECFC program divided participants into three categories: essential family supports, essential supports for employment and independent living, and comprehensive supports for employment and community living. (Two other categories for those with intensive behavioral health needs were added later.) Each group has access to a different benefit package and annual expenditures are capped at different dollar amounts. All children who live at home with their families receive the essential family supports benefit as do some adults who choose that benefit. All other adults receive one of the other two benefits depending on whether they qualify for nursing home placement. All three benefits include services that support caregivers (e.g., respite care and community transportation). However, the essential family supports benefit consists almost entirely of services to support and sustain the family caregiver in supporting the participant (e.g., caregiver stipend in lieu of supportive home care and health insurance counseling/forms assistance) while the other two benefit groups are aimed mostly at helping the participant (and supporting the caregiver to help the participant) achieve employment and integrate into the community (e.g., job coaching and independent living skills training).

Washington State’s coverage of a caregiver benefit package. In 2017, Washington established two benefits that include services for family caregivers. For the first five years of the program, both benefits are paid for by federal Medicaid funding under the state’s 1115 waiver. The Medicaid Alternative Care (MAC) benefit is targeted to older adults (55 and older) who qualify for Medicaid-financed LTSS but have chosen to wrap services around their unpaid caregiver rather than receive traditional Medicaid-funded services. The Tailored Supports for Older Adults (TSOA) benefit targets older adults who are not currently Medicaid-eligible but are at-risk for future Medicaid-financed LTSS use. TSOA offers two packages of services. If the older adult has an unpaid caregiver, the adult receives a package that consists solely of supports for the benefit of the caregiver. If the older adult does not have an unpaid caregiver, the package offers services, such as in-home personal care, to the older adult. According to state officials, the ability to offer enrollees a choice of individual or caregiver benefits (rather than a package that included both individual and caregiver benefits) has been critical to making the program work for both enrollees and the legislature. This option, which is currently only available under an 1115 waiver, like the concept of rebalancing the LTSS system puts choice in the hands of the enrollee and offers the opportunity for cost savings because the caregiver benefit is much less costly than the individual benefit.

The two benefit packages are almost identical, with both including the following services targeted to the caregiver.

- Caregiver assistance services, are defined as, “Services that take the place of those typically performed by the unpaid caregiver in support of unmet needs the care receiver has for assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living,” such as home delivered meals.

- Caregiver training and education, is defined as, “Services and supports to assist caregivers with gaining skills and knowledge to implement services and supports needed by the care receiver to remain at home or skills needed by the caregiver to remain in their role,” such as caregiver coping training and caregiver clinical training.

- Health maintenance and therapies, are defined as, “Clinical or therapeutic services that assist the care receiver to remain in their home or the caregiver to remain in their caregiving role and provide high quality care,” such as counseling.

Other services are also included in the benefits that are primarily targeted to the care recipient. but also support the caregiver and the TSOA package, which serves people who are not yet eligible for Medicaid and also offers personal assistance services to the care receiver. These benefits are both self-directed and, within the assigned budget, services are selected based on both enrollee and caregiver need.

Over a six-month period, caregivers who received support from these programs showed a statistically significant improvement in outcomes such as, stress burden, comfort with the care giver roles and depression. Also, there are indications that participation in these programs delayed the need to access Medicaid LTSS.[49] In 2019, Washington’s TSOA served a total of 1,574 dyads (caregiver/care receiver) and 3,033 individuals at a total cost of about $8.5 million; during this same time Washington served 142 MAC dyads at a cost of about $166,272. Officials indicated that the cost of the programs was offset by reductions in the need for LTSS.[50]

Facilitate family caregivers’ ability to receive payment for the services they provide.

As described in the Medicaid primer section, states can use multiple federal authorities to implement self-directed care in HCBS, which enables enrollees to use Medicaid funding to pay aides of their choice, including family caregivers for the services they provide. All but one state has implemented these provisions for at least some enrollees who receive HCBS.[51] However, there are barriers to payment even within these programs, which some states have moved to address.

Colorado’s waiver of scope of practice laws to enable family caregivers to provide skilled health-related activities. Colorado has addressed the barrier that state scope-of-practice laws can sometimes pose to family caregiver payment. This state offers in home support services (IHSS) as a benefit in three of its 1915(c) waivers, so the service is available to both children and adults. IHSS is a self-directed benefit, so waiver participants can choose family caregivers to serve as their paid attendants. However, an IHSS agency acts as the enrollee’s agent — hiring, training, and paying the caregiver/employee. If the participant chooses the family caregiver as an attendant, this unlicensed caregiver can be paid for providing health maintenance services, including assistance with skilled health-related activities (e.g., skilled feeding or skilled bowel care) that are typically provided by a certified or licensed attendant. Colorado waived the Nurse Practice Act for IHSS, which is what enables the unlicensed caregiver to be paid for providing the skilled services. All IHSS agencies must employ a registered nurse who is responsible for verifying the caregiver’s skills and competency. Waiver participants may receive up to 40 hours of personal care from a relative each week. They can also receive more personal care from other providers.[52]

Idaho’s program integrity process recognizes the unique situation of family caregivers. An important aspect of facilitating payment to family caregivers is to maintain public support for these payments. Therefore, maintaining program integrity (preventing fraud, waste, and abuse of Medicaid funds) is key to facilitating caregiver payment over the long term. As one state official observed, the vast majority of family caregivers comply with Medicaid program rules and bill appropriately. But a few people do take advantage of the system, which can be very problematic, especially if these cases are reported in the media. Idaho officials, recognizing that paid family caregivers usually provide services to only one person, understand that caregivers might not follow all program rules simply because they do not understand the complexities of Medicaid billing. Idaho Medicaid staff work very closely with the family members to ensure that they understand the complicated process of employer records and documentation. Family caregivers often provided the same care without pay before being tapped by their family member to provide paid care. So, one shift that can be difficult is moving from simply providing the care to both providing the care and documenting their time for billing purposes. Idaho has also established close connections between the team that trains the caregiver on Medicaid billing and the program integrity team so that program integrity staff can help improve training for family members who are now providers.

How Can the Federal Government Help States Implement Family Caregiver Strategies?

The actions for federal consideration described here were developed by the authors based on previous NASHP work in this area, their knowledge of state health policy, presentations and discussions at the RAISE advisory council meetings, and significant input from state policymakers. These actions would enable the federal government to help states build on the many strategies that states are already using to support family caregivers. They are not intended as stand-alone actions but rather a package that would culminate in widespread state adoption of innovative practices.

When considering these actions, it is important to understand that the current top priorities of most Medicaid officials are to address the COVID-19 pandemic and plan for related state budget reductions. As a result, it is unlikely that states will choose to implement bold new initiatives, especially those that require upfront investments, now. However, there are factors that could lead states to consider new strategies even in these challenging times. States are already making a financial investment in family caregivers who are paid under a self-directed HCBS program and also already have these individual’s contact information. These factors would both ease implementation and strengthen the incentives for states to implement innovations targeted to this group. However, most importantly, the epidemic is taking the greatest toll on nursing facility residents,[53] as well as low-income individuals and communities of color.[54] Family caregivers can provide the culturally and linguistically competent services that help people remain in their own homes and connected to their communities. Increased support for family caregivers, especially supports that improve their ability to care for their loved ones and manage caregiver stress so they can continue to provide that care, could help mitigate the impacts of the virus.

This situation makes the collection of information about state innovations and family caregiver needs and priorities particularly important as this information would enable states to understand the costs and benefits of their options for support, as well as target those efforts to the specific needs of Medicaid enrollees’ family caregivers. States would also be more likely to quickly adopt these strategies if there was an associated implementation funding strategy, such as that created for the BIP or a dedicated technical assistance center, such as those created to support other national efforts.

Action 1: Conduct a comprehensive, systematic effort to identify and disseminate information about family caregiver strategies tested by states. This report has identified state innovations that address five critical issues in family caregiver support. These issues and innovations are just the first step in identifying the full scope of state innovations. It is expected that other states have also developed innovations that address these and other critical issues that authors were unable to identify during the writing of this report. Because states differ in terms of operating authority, delivery systems, and policy environment, the same innovation is unlikely to work well in all states. Therefore, states seeking to improve family caregiver support by adopting tested strategies would benefit from access to a more comprehensive toolbox of promising practices. Ideally, the information in the toolbox would offer states sufficient information to assess their options and begin developing their own plans, type of support, target population, key partners, federal authority used, implementation cost, expected impact on state budget, anticipated and confirmed outcomes, etc. The state officials who reviewed this report emphasized the importance of having information that details strategy effectiveness for their decision making. The federal agencies dedicated to research, such as the office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging Policy, could commission this initiative.

Action 2: Measure the number, demographic, contribution, and needs of family caregivers who assist Medicaid enrollees. Little is known about the demographics, contributions, needs, and priorities of family caregivers who assist Medicaid enrollees as distinct from other caregivers. Nor is there an estimate of the economic value these caregivers provide to states. Many states use the information gathered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to better understand the demographics and needs of caregivers in their state. However, not all states collect caregiver information and the data collected may not be specific to caregivers of Medicaid enrollees. A few states have made efforts to collect data about Medicaid enrollees’ family caregivers and their needs. Texas, for example, gathers information on caregivers (demographics, hours provided, stress level, effect on employment, etc.) for a state legislative report as part of the assessment process, but it does not track caregiver needs. Also, as Tennessee discovered, family caregivers’ assessment of which services would help them most differed from that of providers and officials themselves. A better understanding of the needs, priorities, and contributions of those who care for Medicaid enrollees would enable states to more efficiently and effectively target their efforts to implement caregiver supports. States would also benefit from assistance, such as toolkits or templates, that would help them use this information to select, implement, and evaluate current or future strategies. The information presented to the RAISE advisory council members in May, as well as their discussion of that information provides a good starting point for this effort. For example, changes to existing national data collection efforts, such as BRFSS, could create an avenue for collecting Medicaid-specific caregiver data.

Action 3: Promote innovative family caregiver support strategies already tested by leading states. Much of this report is dedicated to exploring a sampling of the strategies and innovations that state Medicaid agencies have already implemented to support family caregiving.  They illustrate the depth and breadth of existing state efforts to support family caregivers across the lifespan. However, not all of these strategies, especially those in the Medicaid innovations section, are broadly used by states currently. Family caregiver support across the United States could be strengthened simply by spreading tested state innovations among states.

They illustrate the depth and breadth of existing state efforts to support family caregivers across the lifespan. However, not all of these strategies, especially those in the Medicaid innovations section, are broadly used by states currently. Family caregiver support across the United States could be strengthened simply by spreading tested state innovations among states.

Because supporting family caregivers can help Medicaid meet its objectives, it is expected that more states would implement these innovations if they were encouraged to do so and had the resources. But not every innovation is right for every state, and one aspect of the assistance that the federal government could provide is helping states make data-driven decisions about which strategies would work best in their state. The federal government could use its resources to broadly inform other states about these innovations and offer funding to encourage state adoption. Other tools, however, could also foster spread of tested innovations without a major investment of federal resources. For example, developing waiver and SPA templates, such as those developed to support state uptake of Health Homes, could be developed to assist states seeking to adopt certain strategies. CMS also has a portfolio of other technical assistance resources and states could draw on those to ease implementation of specific strategies.

Action 4: Support state efforts to continue to advance their existing innovations and develop new ones. Although, as illustrated in the Medicaid innovations section, some states have developed and tested innovative family caregiver supports, more work is needed. For example, other strategies could be developed to address the critical issues identified in this report in order to begin to develop options that would work under different state circumstances and for different populations (e.g., caregivers to CYSHCN are likely to need different supports than caregivers to older adults). It is expected that leading states will continue to refine and build on their existing family caregiver support strategies. These states have already exhibited a commitment to improving family caregiver support and the federal government has resources to help them do so. These states could leverage the individual technical assistance that CMS staff offers to states, which identifies “promoting community integration through long-term services and supports,” as a program area. These states could also benefit from the type of technical assistance offered by the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program, which has identified “promoting community integration through long-term services and supports,” as a program focus.

Summary

Family caregivers play an important role in states’ efforts to eliminate institutional bias in Medicaid’s LTSS system. Their contributions also offset the cost of personal care services and have the potential to delay institutional admissions and prevent avoidable hospitalizations. All state Medicaid agencies already support family caregivers through training, services, or, sometimes, payment. However, there are strong indications that family caregivers (and the Medicaid enrollees they care for) could benefit from additional supports. Some states have implemented innovative strategies that address critical issues in family caregiver support. An examination of these strategies, research, and input from state officials identified four interdependent actions that the federal government could take to improve family caregiving as part of the national strategy.

- Promote innovative family caregiver support strategies already tested by leading states.

- Support state efforts to continue to advance their existing innovations and develop new ones.

- Conduct a comprehensive, systematic effort to identify and disseminate information about family caregiver strategies tested by states

- Measure the number, demographics, contributions, and needs of the family caregivers who assist Medicaid enrollees.

It is important to acknowledge that the current pandemic and its expected impact on state budgets will, at least temporarily, make it difficult for states to contemplate implementing any new policies, especially those that require upfront investments. The pandemic, however, has also created a window of opportunity during which the federal government can prepare to support states and state officials can use to consider their options.

End Notes

[1] Soucheray, S. (2020). “Nursing homes might account for 40% of US COVID-19 deaths.” University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/06/nursing-homes-might-account-40-us-covid-19-deaths

[2] Gebeloff, R., Lai, K., Oppel, R., Smith, M., Wright, W. (2020). “The Fullest Look Yet at the Racial Inequity of Coronavirus.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/05/us/coronavirus-latinos-african-americans-cdc-data.html