The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated long-standing challenges for states in providing access to high-quality home and community-based services (HCBS).[1] Under the American Rescue Plan Act, the federal government expanded funding to states’ Medicaid HCBS programs, including a one-year, 10-percentage-point increase in federal Medicaid matching funds for HCBS. Nearly three-quarters of states (36 states) plan to allocate these funds specifically toward strengthening youth-serving systems. Strategies include supporting pediatric HCBS providers and caregivers and increasing access to home and community-based behavioral health care. While some select initiatives in state spending plans remain under review, all 50 states have received approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to claim the enhanced Medicaid HCBS Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) and begin to implement their proposals.[2]

Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services for Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs

Home and community-based services include home health care, personal care, and durable medical equipment. HCBS are particularly important for children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN) who, due to their complex conditions, may be at risk of unnecessary placement in hospitals or institutions.[3] Improving access to HCBS can allow CYSHCN to receive services in their home or a community setting and avoid unnecessary residential placement. In addition to improving quality of life for those who receive them, HCBS have also been shown to provide significant cost savings to states when compared with residential care.[4] Over the past several decades, state Medicaid programs have shifted toward providing more services to children with complex needs in the home rather than institutions because of changing policies and federal requirements.[5]

Medicaid plays an important role in providing access to HCBS for CYSHCN. Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term services and supports, which includes HCBS,[6] and as of 2019, Medicaid and CHIP completely or partially covered about 45 percent of CYSHCN.[7] Medicaid is also an important source of coverage for CYSHCN of color. Children and youth with special health care needs enrolled in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are almost three times as likely to be non-Hispanic Black and 1.5 times as likely to be Hispanic than children with private coverage only.[8] As their primary coverage source, Medicaid can play a critical role in improving access to HCBS for CYSHCN, particularly CYSHCN of color.

American Rescue Plan Act and HCBS

The increased risk of serious illness or death from COVID-19 for individuals with complex health care needs and those in congregate settings has reinforced the importance of HCBS.[9] Yet, the ongoing pandemic has exposed existing barriers to accessing HCBS, including workforce shortages, particularly for HCBS providers who serve children with chronic and complex needs.[10] The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), signed into law in March 2021, included provisions to strengthen access to HCBS for Medicaid beneficiaries living with chronic and complex conditions. Section 9817 of the Act provides states with a 10-percentage point increase in their Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid expenditures related to HCBS.[11] ARPA stipulates that the funding must be used to supplement, not replace, existing state funds spent on Medicaid HCBS as of April 1, 2021, and that state funds equivalent to the amount of the increased FMAP can be used to facilitate activities that enhance, expand, or strengthen Medicaid HCBS.[12] The act and subsequent guidance from CMS provide allowable uses of this funding (see text box). Originally, the guidance permitted use of these expanded FMAP funds through March 31, 2024, but this deadline has been extended to March 31, 2025.[13]

States are required to submit an initial HCBS spending plan with semi-annual updates to CMS to receive federal approval for use of the increased funds for HCBS. While states have received approval for their initial plans and the necessary state legislative authority for spending, they continue to navigate the process of updating proposals and distributing funds.

HCBS Plan Requirements and Services Eligible for FMAP Increase under ARPA

According to CMS guidance, states may direct funds from the increased Medicaid FMAP under ARPA to introduce, expand, or strengthen the following allowable HCBS benefits:

- Home health care

- Personal care services (including self-directed)

- Case management

- School-based services

- Rehabilitative services

- Private-duty nursing

- HCBS waiver benefits

Source: State Medicaid Director Letter, CMS Guidance, May 13, 2021[14]

Key Themes in State ARPA HCBS Spending Plans for Children

States are using the enhanced federal HCBS funds through a variety of strategies, some of which reflect considerations for the one-time, time-limited FMAP increase. These include investments in programs without ongoing expenses or upfront costs for newly introduced services. Additionally, some spending plan proposals leverage and build on existing federal and state programs that serve CYSHCN (e.g., Medicaid waivers, Title V Maternal and Child Health Block Grant programs).[15]

A number of states have targeted specific populations that access HCBS (e.g., children, adults, those with specific conditions) in their spending plans, and others have focused on improving HCBS for all beneficiaries. While not required by ARPA, many states solicited input from stakeholder groups in developing their proposed HCBS spending plans. This included at least four states (Arizona, Illinois, Iowa, West Virginia) that specifically collected feedback from families of children who would be affected by improvements to HCBS. Finally, several states are focusing on health equity, specifically racial equity, in their plans.

This analysis covers state strategies specifically targeted to children. States are planning to improve HCBS for youth across a range of services, and many are developing proposals for specific, high-need populations, such as those with medical complexity or those in foster care. Children may also benefit from state proposals to enhance HCBS for the general population, but only youth-focused investments are included in this brief.

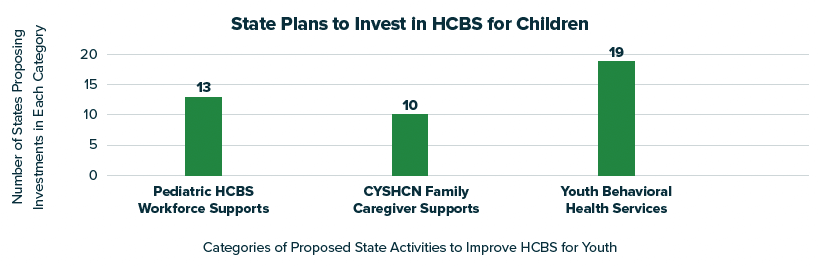

- Of the 36 states planning to invest specifically in children, 13 states include initiatives to strengthen the pediatric HCBS workforce, 10 states identify supports for family caregivers of CYSHCN, and 19 states outline efforts to expand access to home and community-based behavioral health services.

These core categories and approaches reflect states’ shared priorities in helping children and families navigate gaps in the health care system and the lasting impacts of COVID-19. All initial state spending plans are available on the following CMS landing page.

Supporting and Strengthening the Pediatric HCBS Workforce

HCBS providers have historically experienced low wages, limited benefits, stressful working conditions, and a lack of career growth opportunities.[16] During the COVID-19 pandemic, additional obstacles emerged, such as the risk of disease exposure and inaccessibility of child care or in-person schooling for children of providers. These challenges have forced many from their positions, amplifying persistent vacancies and high turnover in the HCBS workforce.[17],[18] In 2021, HCBS workforce shortages were one of the primary concerns for state Medicaid programs, and 25 states indicated the permanent closure of at least one Medicaid HCBS provider.[19] For Medicaid beneficiaries receiving HCBS, workforce shortages restrict the availability of services and often force families to seek residential or institutional care.

About HCBS Providers

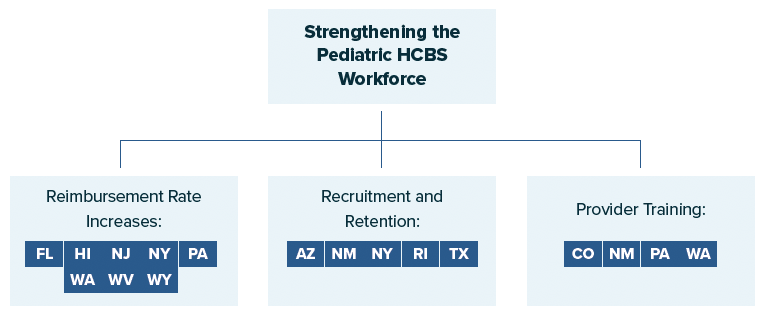

Reimbursement Rate Increases

States are proposing Medicaid reimbursement rate increases as one mechanism to directly support HCBS providers. Insufficient wages are consistently cited as one of the greatest challenges facing the HCBS workforce, and in 2020, nearly half of direct support professionals lived in low-income households.[25] By raising the rates that Medicaid pays for HCBS, states can support the financial needs of pediatric HCBS providers and help strengthen the direct care workforce. Modest Medicaid reimbursement rate increases have been demonstrated to incentivize providers to accept more patients covered by Medicaid and expand their access to services.[26]

Eight states propose increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates for pediatric HCBS providers within the following areas:

- Rate increases for certain waivers: Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Wyoming have outlined their intention to raise rates paid to providers for HCBS covered through specific waivers or state plan amendments. The types of waivers that states are targeting for rate increases include general 1915(c) HCBS waivers for children, a waiver for children with medical complexity, a waiver for children with intensive mental health needs, and a waiver for children who have experienced trauma.

- Rate increases for certain HCBS: Hawaii, New Jersey, New York, and Washington plan to raise rates paid for certain services to support in-demand specialty providers. States are targeting increased provider rates for HCBS such as screenings, applied behavioral analysis for children with autism, case management services for youth with behavioral health needs, and rehabilitative services.

- Rate increases for managed care entities: Washington has proposed directing funds to managed care organizations to increase provider payments for wraparound mental health services for youth.

West Virginia[27] is proposing a temporary 70 percent increase in reimbursement rates for services covered under the state’s Children with Serious Emotional Disorder Waiver, which covers HCBS for youth with severe mental disorders.[28] The increase will go to direct care workers through wage increases, bonuses, and improved benefits.

Recruitment and Retention Initiatives

States are investing in targeted efforts to recruit and retain pediatric providers as another approach to strengthen the HCBS workforce through the enhanced Medicaid FMAP. Attracting new professionals to serve children is vital in filling the significant number of vacancies among direct care workers. Additionally, retaining both newly hired and longer tenured staff can limit the high turnover and shortages experienced during the pandemic.

Five states propose initiatives to recruit and retain HCBS providers who specifically serve children:

- Arizona and Rhode Island plan to deliver direct hiring bonuses to in-demand providers working with children in foster care—two-time payments to new therapeutic foster care providers in Arizona and an hours-based incentive to professionals serving foster youth in Rhode Island.

- New Mexico and Texas intend to finance external entities’ efforts to recruit HCBS providers for youth. New Mexico plans to fund schools to hire providers under the state’s school Medicaid program, while Texas aims to contract with a private entity to recruit direct care workers and collaborate with provider agencies to tackle workforce shortages.

- New York[29] has proposed a comprehensive strategy to recruit and retain youth-serving HCBS providers by allocating $9.28 million through a Children’s Services Workforce Development Fund. The fund will finance activities, such as hiring bonuses, tuition reimbursement and loan forgiveness, and student placement initiatives, to attract new pediatric HCBS providers. Additionally, the proposed fund would cover policies to support the current workforce and incentivize employees to remain in their positions. These include longevity pay, differential pay for certain hours (e.g., evening), professional licensing, and enhanced retirement and health insurance benefits.

Provider Training

For CYSHCN who rely on HCBS, providers must be equipped with the knowledge and expertise to effectively deliver specialized care. Trainings are an essential strategy to supply HCBS providers with the skills necessary to treat all children. Additionally, provider education can expand the services that direct support professionals are qualified to deliver, thereby filling gaps in the children’s services workforce.

Four states plan to train pediatric HCBS providers through the enhanced Medicaid HCBS FMAP. State approaches vary based on which groups of providers are specifically targeted:

- Training for providers serving specific youth populations: Pennsylvania and West Virginia intend to fund trainings for providers who treat certain groups of youth with significant health care needs: children with medical complexity and adolescent sexual abuse victims, respectively.

- Training for specific provider types: Pennsylvania and New Mexico plan to finance trainings for certain types of high-demand pediatric providers, specifically nurses caring for CYSHCN. Additionally, New Mexico plans to expand training for school-based health teams who provide services under Medicaid.

- Training for providers generally: Colorado has proposed directing funds to trainings for HCBS providers on the Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment benefit and quality performance measures related to the program.

Expanding and Improving Youth Behavioral Health Services

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many children have experienced the death of a family member or caregiver,[30]in addition to missing substantial time in schools and opportunities for social interaction. A number of youth have reported increased feelings of depression and unhappiness,[31] and when comparing the first months of the pandemic with the same period in 2019, the proportion of pediatric emergency department visits for mental health-related purposes increased by about 30 percent.[32]

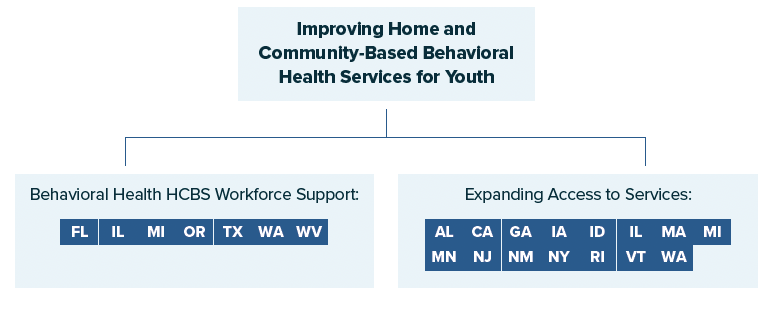

To mitigate these impacts of COVID-19 on children, ensuring access to behavioral health treatment is essential. Policymakers have been increasingly committed to improving home and community-based behavioral health services because they are a key component of the continuum of pediatric behavioral health care and can effectively reduce institutional placement.[33] ARPA expanded the HRSA-funded Pediatric Mental Health Care Access Program, a federal grant program promoting the delivery of telehealth behavioral health services.[34] States have taken action as well, enacting laws[35] and dedicating ARPA funding[36] to improve school mental health systems, an important source of community-based care for children.[37] In addition to these efforts, 19 states—over half of the 36 states specifically devoting ARPA HCBS funding to youth—plan to enhance children’s home and community-based behavioral health services through the Medicaid HCBS FMAP. This includes investments in the behavioral health workforce and new youth mental health-focused HCBS.

Behavioral Health Workforce Supports

While the pandemic has boosted demand for mental health services, behavioral health care staffing shortages have restricted states’ ability to serve those in need.[38] For providers who serve children and youth, these shortages are significant and have been persistent for years.[39] Implementing targeted efforts to support pediatric behavioral health providers can boost the capacity of staff and attract more workers to provide home and community-based mental health services to youth. This can reduce challenges in accessing providers and thereby enhance mental health care for children.

Seven states have proposed efforts to strengthen the children’s home and community-based behavioral health workforce:

- Florida, Illinois, and Oregon intend to expand providers’ capacity to deliver mental health services. Illinois and Oregon have outlined efforts to assist providers with the initial planning of new HCBS for youth with intensive behavioral health needs. This includes financing start-up costs, such as the development of care management platforms, as well hiring clinical expertise to support strategic planning.

- Michigan, Texas, Washington, and West Virginia plan to expand trainings for children’s behavioral health providers. Specific topics targeted for trainings include the diagnosis of mental health disorders, intensive care coordination, cognitive behavioral therapy, and general support for families of youth with behavioral health needs.

Michigan[40] is launching a large-scale reform of its existing pediatric behavioral health system. The state has proposed several initiatives to recruit new providers of home and community-based behavioral health services for children. These include expanding student loan forgiveness and funding paid internships for students working in youth behavioral health shortage areas. Additionally, Michigan plans to finance training for pediatric behavioral health providers in delivering services such as care coordination. The state has outlined a Children’s Behavioral Health Provider Learning Community that will initiate peer-to-peer collaboration and training between providers.

Promoting Access to Behavioral Health Services

Prior to the pandemic, nearly half of children with a mental health disorder did not receive treatment from a mental health professional.[41] With needs among youth and delays in care rising due to COVID-19, access to services is a growing concern. Expanding the availability of behavioral health care is an essential approach that states are embracing to better connect children to mental health treatment.

Fifteen states intend to promote access to home and community-based behavioral health services for youth, including providing new behavioral health benefits for children and bolstering current programs:

- Alabama, Georgia, Iowa, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey plan to establish new HCBS for youth with behavioral health needs, either through expanding types of care that are reimbursable or creating new community-based care models. These states intend to promote access to care by introducing services such as in-home behavioral health aids, therapeutic support services, and mental health services for youth with disabilities or in foster care.

- Idaho and New York have expressed an intention to provide additional funding to bolster existing home and community-based behavioral health benefits for youth. Michigan, New Mexico, Illinois, and Rhode Island have each proposed similar strategies to enhance existing benefits but specifically for care coordination and case management for children with mental health needs. These services can help families manage their children’s care and facilitate access to treatment. California, Minnesota, and Rhode Island will bolster existing benefits that support youth with behavioral health needs who are transitioning from institutional care or the juvenile justice system.

- Idaho, Massachusetts, Michigan, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington plan to invest in community-based behavioral health crisis response services to support youth with urgent behavioral health needs. Approaches include creating new crisis intervention programs that specifically serve youth, improving funding of existing response services, supporting implementation of 988 suicide prevention hotlines, and expanding local pediatric crisis intervention teams.

Rhode Island[42] is proposing a renovation of its Behavioral Health System of Care[43] for youth. The state intends to remove HCBS waitlists for families and create community care partnerships to improve care coordination and transition services for youth with behavioral health needs. Additionally, Rhode Island’s proposal includes efforts to expand the state’s hotline on children’s behavioral health and establish it as a central point for families navigating the behavioral health system. Strengthening this hotline would provide one location for crisis response, as well as referrals to mental health treatment from schools, hospitals, or community programs and could facilitate communication between youth mental health providers and families.

Supporting Family Caregivers

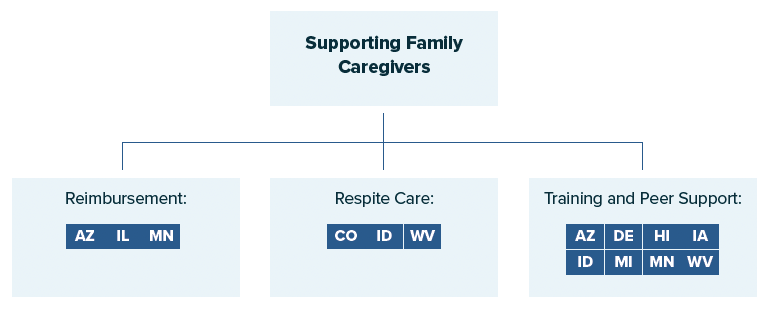

Family caregivers play an important role in serving children with chronic and complex needs. Family caregivers of CYSHCN spend 29.7 hours on average per week providing care, with 24 percent of caregivers providing at least 41 hours of care per week.[44] Shortages of qualified HCBS providers available to serve CYSHCN have made family caregivers an even more critical component in keeping CYSHCN in home and community-based settings.

While many states have focused on supporting family caregivers of adults[45], 10 states have specifically included supports for family caregivers of children in their HCBS state spending plans. These strategies include establishing or improving reimbursement of family caregivers, providing respite services for family caregivers, and providing training and peer supports to caregivers.

Establishing or Improving Reimbursement for Family Caregivers

Family caregivers often face unique challenges in the care of their child or family member, including lack of financial support. Policies that promote Medicaid reimbursement of family caregivers can help alleviate home health provider workforce shortages while potentially reducing costs for the state, depending on how reimbursement rates for family caregivers are balanced against increased oversight costs.[46] Three states have proposed using the increased FMAP funds under ARPA to enhance access to HCBS by providing reimbursement specifically for family caregivers of children:

- Arizona and Minnesota both granted temporary authority made available through the public health emergency to implement programs that pay family caregivers of children in their Medicaid programs. In their ARPA spending plans, these states are proposing to extend this provision beyond the termination of the public health emergency. Minnesota is also planning to increase the rates paid to families under their program.

- Illinois[47] is proposing the establishment of a paid family caregiver benefit under their Medically Fragile/Technology Dependent Children wavier by using $2.5 million in ARPA funds. This waiver serves individuals who enrolled prior to turning 21 years old that, due to disability or illness, require “the level of care appropriate to a hospital or skilled nursing facility without the support of services provided under the waiver.”[48] The family caregiver benefit would allow unlicensed parents to receive payments from Medicaid, and these payments could be part of the beneficiary’s current resource allocation. The funds provided under the additional FMAP would be used to support the administrative and structural activities needed to operationalize the benefit, including monitoring quality and providing training.[49] Illinois’ decision to devote funding to this effort was informed by their stakeholder engagement process and a series of focus groups with families of children with medical complexities.

Respite Care for Family Caregivers

Providing ongoing care to children with medically complex conditions can be overwhelming and have a mental and physical impact on family caregivers.[50] Respite care provides temporary services for individuals with special health care needs, with the purpose of relieving their primary caregiver. Respite care is an important aspect of HCBS for children as it can enable a child to remain in their home or community-based setting by supporting their primary caregiver, who may have additional children that they are caring for or another job outside the home. Finding accessible pathways to respite care and providers qualified to serve children’s needs can be a challenge.[51]

Three states plan to use their enhanced Medicaid HCBS FMAP under APRA to support respite care for children’s caregivers through a variety of strategies:

- Colorado plans to increase the number of respite providers who are qualified and available to serve children with complex needs by providing a temporary incentive payment to respite workers who agree to serve children.

- Idaho plans to use ARPA funds to provide supplemental payments to HCBS providers, including respite care providers who serve children with serious emotional disturbances and children with disabilities in two 1915(i) Medicaid waivers.[52] Financial support of respite providers is a key element of Idaho’s plan to increase funding to different types of HCBS providers. By including respite providers in this workforce recruitment and retention strategy, Idaho is prioritizing them as an important component of HCBS and an essential resource to support parents caring for their children in a home-based setting.

- West Virginia plans to finance training for additional respite providers to serve families of children with specific behavioral health needs.

Training and Peer Support for Families of CYSHCN

Providing training and peer support to families of CYSHCN can ensure they are given the tools and resources they need to continue caring for their child in a home or community-based setting and avoid residential placements. The value of peer supports for families of children with complex needs is widely documented and evidence based.[53] Seven states(Arizona, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, and West Virginia) propose efforts to provide training and peer support for family caregivers, particularly those with children with complex health care needs.

Hawaii plans to establish a new family-to-family peer support service in its Medicaid 1915(c) Home and Community-Based Services waiver for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). This service would connect family caregivers of children with disabilities with peers who have lived experience and are trained to support them.[54] Hawaii also plans to sustain peer supports beyond the ARPA funding by incorporating ongoing costs into their I/DD waiver budget.

Key Considerations

With full CMS approval to claim the enhanced Medicaid HCBS FMAP, states have begun implementing proposals from their spending plans.[55] There are several considerations for states as they move forward with distribution of funds to improve HCBS for Medicaid beneficiaries:

- Account for the one-time nature of ARPA funding and the FMAP increase. The Medicaid HCBS FMAP increase under ARPA is one-time and time-limited. In maximizing the sustainability and effectiveness of investments, states will have to account for the temporary nature of these funds. Some states have detailed more upfront, short-term HCBS investments, while others have strategically proposed programs without ongoing costs. Additionally, several proposals outline potential avenues to preserve funding for newly established HCBS initiatives beyond March 2025, a strategy that may be useful in promoting sustainability.

- Monitor legislative action around HCBS funding and adjust activities as needed. Federal lawmakers have proposed bills to further support states in planning and delivering HCBS. New federal investments in HCBS may allow states to extend or build on their proposals to serve children through the enhanced FMAP. Additionally, at the state level, legislative sessions may provide states with an opportunity to address funding for Medicaid HCBS and distribute additional federal funds to supplement home and community-based activities.

- Address the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on HCBS and children’s needs. As states begin the recovery phase of their COVID-19 response, children continue to experience restricted access to HCBS and health risks associated with the pandemic.[56] At the same time, the public health emergency and its Medicaid continuous enrollment requirement—which prohibits states from disenrolling individuals from Medicaid during this period—will be ending in the coming months.[57] Many children will be vulnerable to losing coverage due to changes in eligibility or paperwork issues.[58] As recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic continues and the public health emergency comes to a close, states will want to continue to collect and monitor data on health system challenges, [59] including HCBS workforce shortages, changes in care utilization, and children’s health needs, particularly their growing behavioral health concerns. Additionally, states can continue to engage families in dialogue around the pandemic’s long-term effects on youth. Continuous assessment of the impacts of the pandemic on children’s health can equip states with the tools to proactively propose investments in Medicaid HCBS and ensure maximum service quality for families.

- Prioritize health equity in all efforts to improve HCBS. Because the pandemic has disproportionately affected families of CYSHCN,[60] communities of color,[61] and low-income populations,[62] states will want to ensure they are addressing health equity in their HCBS improvement efforts. States can collect data on the impacts of COVID-19 and access to HCBS across characteristics such as race, ethnicity, disability status, and income level and target expansions of HBCS to communities where inequities are most prevalent. Additionally, outlining the importance of health equity in HCBS and prioritizing it in any initiatives and strategic planning will be a key approach to ensure that those with the greatest need have access to care.

- Monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of approaches to improve HCBS. As states utilize the enhanced FMAP, continuous evaluation of the impacts of efforts to improve HCBS can help in determining which strategies to supplement further, maintain, or modify. States may also be able to apply strategies with demonstrated effectiveness to alleviate broader challenges in their Medicaid programs, such as provider shortages. Approaches that states can consider to evaluate impact include collecting and analyzing data around access to providers, particularly those serving youth. States can also engage families and HCBS providers in bidirectional feedback to obtain data on the perceived effects of investments in HCBS improvements.

HCBS are essential for children and adults, who often benefit from receiving care within their home or community rather than institutional settings. NASHP will continue to monitor and analyze states’ HCBS plans and the implementation of new and enhanced home and community-based programs.

References

[1] O’Malley Watts, Molly, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Meghana Ammula. “State Medicaid Home & Community-Based Services (HCBS) Programs Respond to COVID-19: Early Findings from a 50-State Survey.” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 10, 2021. www.kff.org/report-section/state-medicaid-home-community-based-services-hcbs-programs-respond-to-covid-19-early-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-issue-brief.

[2] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Strengthening and Investing in Home and Community Based Services for Medicaid Beneficiaries: American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 Section 9817 Spending Plans and Narratives.” Medicaid.gov. www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/home-community-based-services/guidance/strengthening-and-investing-home-and-community-based-services-for-medicaid-beneficiaries-american-rescue-plan-act-of-2021-section-9817-spending-plans-and-narratives/index.html; Weber, Lauren, and Andy Miller. “Why Billions in Medicaid Funds for People with Disabilities Are Being Held Up.” National Public Radio, March 2, 2022, sec. Policy-ish. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2022/03/02/1083792436/why-billions-in-medicaid-funds-for-people-with-disabilities-are-being-held-up.

[3] Keim-Malpass, Jessica, Leeza Constantoulakis, and Lisa C. Letzkus. “Variability In States’ Coverage of Children with Medical Complexity Through Home and Community-Based Services Waivers.” Health Affairs 38, no. 9 (September 1, 2019): 1484–90. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05413.

[4] National Council on Disability. “Costs in Detail.” July 22, 2015, sec. Deinstitutionalization Toolkit. https://ncd.gov/publications/2012/DIToolkit/Costs/inDetail.

[5] O’Keeffe, Janet, Paul Saucier, Beth Jackson, Robin Cooper, Ernest McKenney, Suzanne Crisp, and Charles Moseley. “Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer, 2010 Edition.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, October 28, 2010. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/understanding-medicaid-home-community-services-primer-2010-edition-0; Musumeci, MaryBeth, Priya Chidambaram, and Molly O’Malley Watts. “Medicaid Financial Eligibility for Seniors and People with Disabilities: Findings from a 50-State Survey.” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 14, 2019. www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-financial-eligibility-for-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/; United States Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. “Olmstead: Community Integration for Everyone.” Information and Technical Assistance on the Americans with Disabilities Act. Accessed April 29, 2022. www.ada.gov/olmstead/olmstead_about.htm.

[6] O’Malley Watts, Molly, Priya Chidambaram, and MaryBeth Musumeci. “Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Enrollment and Spending.” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 4, 2020. www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-enrollment-and-spending-issue-brief.

[7] Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. “2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health (NCSH).” Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey/results?q=8595&r=1&g=921.

[8] Williams, Elizabeth, and MaryBeth Musumeci. “Children with Special Health Care Needs: Coverage, Affordability, and HCBS Access.” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 4, 2021. www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/children-with-special-health-care-needs-coverage-affordability-and-hcbs-access.

[9 ] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “People with Certain Medical Conditions.” CDC.gov, May 2, 2022. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html.

[10] O’Malley Watts, Molly, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Meghana Ammula. “State Medicaid Home & Community-Based Services (HCBS) Programs Respond to COVID-19: Early Findings from a 50-State Survey.” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 10, 2021. www.kff.org/report-section/state-medicaid-home-community-based-services-hcbs-programs-respond-to-covid-19-early-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-issue-brief.

[1q] Congress.gov. “H.R.1319 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.” March 11, 2021. www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text.

[12] Purington, Kitty, and Danielle Owens. “State Opportunities to Strengthen Home and Community-Based Services through the American Rescue Plan.” National Academy for State Health Policy, June 1, 2021. www.nashp.org/state-opportunities-to-strengthen-home-and-community-based-services-through-the-american-rescue-plan.

[13] Tsai, Daniel. “SMD# 22-002 RE: Updated Reporting Requirements and Extension of Deadline to Fully Expend State Funds Under American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 Section 9817.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, June 3, 2022. www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd21003.pdf.

[14] Costello, Anne Marie. “SMD# 21-003 RE: Implementation of American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 Section 9817: Additional Support for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services during the COVID-19 Emergency.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, May 13, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd21003.pdf.

[15] Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. “Illinois Initial Spending Plan and Narrative for Enhanced Funding under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 to Enhance, Expand, and Strengthen Home and Community-Based Services under the Medicaid Program,” July 12, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/il-arp-hcbs-enhanced-07-12-21.pdf.

[16] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. “Direct Services Workforce Shortages during COVID-19.” PHE.gov, February 2, 2021. www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Pages/Direct-Services-Workforce-Shortages-during-COVID-19.aspx.

[17] Human Services Research Institute, and National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services. “2019 National Core Indicators Staff Stability Survey Report.” National Core Indicators, 2020. www.nationalcoreindicators.org/upload/core-indicators/2019StaffStabilitySurveyReport_FINAL_1_6_21.pdf.

[18] O’Malley Watts, Molly, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Meghana Ammula. “State Medicaid Home & Community-Based Services (HCBS) Programs Respond to COVID-19: Early Findings from a 50-State Survey.” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 10, 2021. www.kff.org/report-section/state-medicaid-home-community-based-services-hcbs-programs-respond-to-covid-19-early-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-issue-brief.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Khatutsky, Galina, Joshua Wiener, Wayne Anderson, Valentina Akhmerova, Andrew Jessup, and Marie R. Squillace. “Understanding Direct Care Workers: A Snapshot of Two of America’s Most Important Jobs—Certified Nursing Assistants and Home Health Aides.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, February 28, 2011. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/understanding-direct-care-workers-snapshot-two-americas-most-important-jobs-certified-nursing-0.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Virginia Department for Aging and Rehabilitative Services, Division for Community Living, Office for Aging Services. “Home & Community-Based Services.” www.vda.virginia.gov/homecbs.htm.

[23] New York State Office of Mental Health, Office of Addiction Services and Supports. “Adult Behavioral Health Home and Community Based Services (BH HCBS) Provider Manual,” February 17, 2022. https://omh.ny.gov/omhweb/bho/docs/hcbs-manual.pdf.

[24] National Academy for State Health Policy. “States Use American Rescue Plan Act Funds to Strengthen Home and Community-Based Service Workforce,” October 14, 2021. www.nashp.org/states-use-american-rescue-plan-act-funds-to-strengthen-home-and-community-based-service-workforce.

[25] PHI. “Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts,” September 7, 2021. www.phinational.org/resource/direct-care-workers-in-the-united-states-key-facts-2.

[26] Alexander, Diane, and Molly Schnell. “The Impacts of Physician Payments on Patient Access, Use, and Health.” National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2020. www.nber.org/papers/w26095.

[27] West Virginia Department of Health & Human Resources, Bureau for Medical Services. “Spending Plan for Implementation of American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Section 9817: Additional Support for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services during the COVID-19 Emergency,” August 12, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/wv-state-arp-hcbs-spending-2021-08-12.pdf.

[28] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “West Virginia Waiver Factsheet.” Medicaid.gov. www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/demonstration-and-waiver-list/Waiver-Descript-Factsheet/WV.

[29] New York State Department of Health. “Spending Plan for Implementation of American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Section 9817: Additional Support for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services during the COVID-19 Emergency,” July 8, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/nys-hcbs-spending-plan-draft0.pdf.

[30] Hillis, Susan D., Alexandra Blenkinsop, Andrés Villaveces, Francis B. Annor, Leandris Liburd, Greta M. Massetti, Zewditu Demissie, et al. “COVID-19–Associated Orphanhood and Caregiver Death in the United States.” Pediatrics 148, no. 6 (December 1, 2021): e2021053760. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-053760.

[31] Margolius, Max, Alicia Doyle Lynch, Elizabeth Pufall Jones, and Michelle Hynes. “The State of Young People during COVID-19: Findings from a Nationally Representative Survey of High School Youth.” America’s Promise Alliance, June 2020. www.americaspromise.org/sites/default/files/d8/YouthDuringCOVID_FINAL%20%281%29.pdf.

[32] Leeb, Rebecca T., Rebecca H. Bitsko, Lakshmi Radhakrishnan, Pedro Martinez, Rashid Njai, and Kristin M. Holland. “Mental Health-Related Emergency Department Visits Among Children Aged <18 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, January 1–October 17, 2020.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020 69, no. 45 (November 13, 2020): 1675–80.

[33] Cidav, Zuleyha, Steven C Marcus, and David S Mandell. “Home- and Community-Based Waivers for Children with Autism: Effects on Service Use and Costs.” Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 52, no. 4 (August 2014): 239–48. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-52.4.239.

[34] Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. “Pediatric Mental Health Care Access (PMHCA),” March 2022. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/training/projects.asp?program=34.

[34] Randi, Olivia, and Zack Gould. “States Take Action to Address Children’s Mental Health in Schools.” The National Academy for State Health Policy, February 14, 2022. www.nashp.org/states-take-action-to-address-childrens-mental-health-in-schools.

[36] Randi, Olivia. “American Rescue Plan Act Presents Opportunities for States to Support School Mental Health Systems.” National Academy for State Health Policy, August 2, 2021. www.nashp.org/american-rescue-plan-act-presents-opportunities-for-states-to-support-school-mental-health-systems.

[37] Hoover, Sharon, and Jeff Bostic. “Schools as a Vital Component of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health System.” Psychiatric Services 72, no. 1 (January 1, 2021): 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900575.

[38] Antezzo, Mia. “Investments in Behavioral Health Service Systems: Top Three Emerging Themes from State Home and Community-Based Services Spending Plans.” National Academy for State Health Policy, October 18, 2021. www.nashp.org/investments-in-behavioral-health-service-systems.

[39] Health Resources and Services Administration. “Shortage Areas.” data.HRSA.gov, June 19, 2022. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas.; Axelson, David. “Beyond A Bigger Workforce: Addressing the Shortage of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists.” Pediatrics Nationwide, April 10, 2020. https://pediatricsnationwide.org/2020/04/10/beyond-a-bigger-workforce-addressing-the-shortage-of-child-and-adolescent-psychiatrists.

[40] Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. “Michigan Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) Spending Plan: American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) Enhanced Federal Funding,” July 12, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/mi-mdhhs-hcbs-spending-plan.pdf.

[41] Whitney, Daniel G., and Mark D. Peterson. “US National and State-Level Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders and Disparities of Mental Health Care Use in Children.” JAMA Pediatrics 173, no. 4 (April 1, 2019): 389–91. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399.

[42] State of Rhode Island. “Spending Plan for Implementation of American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Section 9817: Additional Support for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services during the COVID-19 Emergency,” July 9, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/ri-spending-plan-arpa-hcbs0.pdf.

[43] The Executive Office of Health and Human Services, State of Rhode Island. “Children’s Behavioral Health System of Care,” March 22, 2022. https://eohhs.ri.gov/initiatives/childrens-behavioral-health-system-care.

[44] National Alliance for Caregiving, and AARP. “Caregivers of Children: A Focused Look at Those Caring for A Child with Special Needs Under the Age of 18,” December 1, 2009. https://doi.org/10.26419/res.00062.007.

[45] The National Academy for State Health Policy. “Map: ARPA Initial Plan Proposed Supports for Family Caregivers,” November 22, 2021. www.nashp.org/map-arpa-initial-plan-proposed-supports-for-family-caregivers.

[46] Randi, Olivia, Eskedar Girmash, and Kate Honsberger. “State Approaches to Reimbursing Family Caregivers of Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs through Medicaid.” National Academy for State Health Policy, January 2021. www.nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Family-Caregivers-for-CYSHCN-PDF-1-15-2021.pdf.

[47] Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. “Illinois Initial Spending Plan and Narrative for Enhanced Funding under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 to Enhance, Expand, and Strengthen Home and Community-Based Services under the Medicaid Program,” July 12, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/il-arp-hcbs-enhanced-07-12-21.pdf.

[48] Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. “Medically Fragile/Technology Dependent Children.” www2.illinois.gov/hfs/MedicalClients/HCBS/Pages/tdmfc.aspx.

[49] Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. “Illinois Initial Spending Plan and Narrative for Enhanced Funding under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 to Enhance, Expand, and Strengthen Home and Community-Based Services under the Medicaid Program,” July 12, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/il-arp-hcbs-enhanced-07-12-21.pdf.

[50] Whitmore, Kim E, and Julia Snethen. “Respite Care Services for Children with Special Healthcare Needs: Parental Perceptions.” Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing: JSPN 23, no. 3 (July 2018): e12217–e12217. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12217.

[51] Cooke, Emma, Valerie Smith, and Maria Brenner. “Parents’ Experiences of Accessing Respite Care for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) at the Acute and Primary Care Interface: A Systematic Review.” BMC Pediatrics 20, no. 1 (May 22, 2020): 244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02045-5.

[52] Idaho Department of Health and Welfare. “Idaho Initial American Rescue Plan (ARP) Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Spending Plan and Narrative,” June 14, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/id-medicaid-arp-spending-plan.pdf.

[53] Obrochata, Carol, Bruno Anthony, Mary Armstrong, Jane Kallal, Joe Anne Hust, and Joan Kernan. “Family-to-Family Peer Support: Models and Evaluation.” Outcomes Roundtable for Children and Families, September 2012. www.fredla.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Issue-Brief_F2FPS.pdf.

[54] State of Hawaii, Department of Human Services. “Spending Plan for Implementation of American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Section 9817: Additional Support for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services during the COVID-19 Emergency,” July 8, 2021. www.medicaid.gov/media/file/hi-spending-plan-for-implementation.pdf.

[55] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Strengthening and Investing in Home and Community-Based Services for Medicaid Beneficiaries: American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 Section 9817 Spending Plans and Narratives.” Medicaid.gov. www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/home-community-based-services/guidance/strengthening-and-investing-home-and-community-based-services-for-medicaid-beneficiaries-american-rescue-plan-act-of-2021-section-9817-spending-plans-and-narratives/index.html

[56] Blumenthal, David, Elizabeth J. Fowler, Melinda Abrams, and Sara R. Collins. “COVID-19—Implications for the Health Care System.” New England Journal of Medicine 383, no. 15 (October 8, 2020): 1483–88. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb2021088.

[57] Tsai, Daniel. “SHO# 22-001 RE: Promoting Continuity of Coverage and Distributing Eligibility and Enrollment Workload in Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Basic Health Program (BHP) Upon Conclusion of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency,” March 3, 2022. www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho22001.pdf.

[58] Alker, Joan, and Tricia Brooks. “Millions of Children May Lose Medicaid: What Can Be Done to Help Prevent Them From Becoming Uninsured?” Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, Center for Children and Families, February 17, 2022. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2022/02/17/millions-of-children-may-lose-medicaid-what-can-be-done-to-help-prevent-them-from-becoming-uninsured.

[59] Blumenthal, David, Elizabeth J. Fowler, Melinda Abrams, and Sara R. Collins. “COVID-19—Implications for the Health Care System.” New England Journal of Medicine 383, no. 15 (October 8, 2020): 1483–88. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb2021088.

[60] Houtrow, Amy, Debbi Harris, Ashli Molinero, Tal Levin-Decanini, and Christopher Robichaud. “Children with Disabilities in the United States and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine 13, no. 3 (2020): 415–24. https://doi.org/10.3233/PRM-200769.

[61] Adhikari, Samrachana, Nicholas P. Pantaleo, Justin M. Feldman, Olugbenga Ogedegbe, Lorna Thorpe, and Andrea B. Troxel. “Assessment of Community-Level Disparities in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infections and Deaths in Large US Metropolitan Areas.” JAMA Network Open 3, no. 7 (July 28, 2020): e2016938–e2016938. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16938.

[62] Ibid.

Acknowledgements

This policy brief was written by Zack Gould and Kate Honsberger. The National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) extends its thanks and appreciation to officials from state Medicaid programs and the Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, for their review.

This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number UD3OA22891, National Organizations of State and Local Officials. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. government.